A much abridged version of this account of attending the urs (April 2019) was shared in Nowhere Magazine in 2020. The visit occurred on an assignment to update the Insight Guide Pakistan (2020).

It was well after midnight when we stepped off the train from Karachi in dusty Sehwan, an otherwise peaceful railroad town on the Indus’ west bank, but teeming with pilgrims that mid-spring night. Leading up to the 18th of Shaʿban (the month before Ramadan) each year, Sehwan’s population swells by orders of magnitude for the urs (from Arabic ʿurs, or ‘wedding’). It’s a ‘marriage celebration’ in which the saint renews his vows with the divine, held on the anniversary of the saint’s death. In this case, the saint is among Pakistan’s most beloved Sufi legends: Lal Shahbaz Qalandar.

In common with most other attendees, I’d come with the goal of paying a visit to his mazar (mausoleum), a golden-domed complex at the center of town. But there are plenty more reasons for coming to noble Sehwan. Some come seeking cures to illness or grief, to exorcise jinn through dancing dhamaal, to attain fana’—annihilation’ of the self into their beloved saint and murshid (guide), seen as a mirror to God. And then plenty of the three-day festival’s patrons, I’d learn, were there at least as much as anything for the late-night parties that rage at the edges of town.

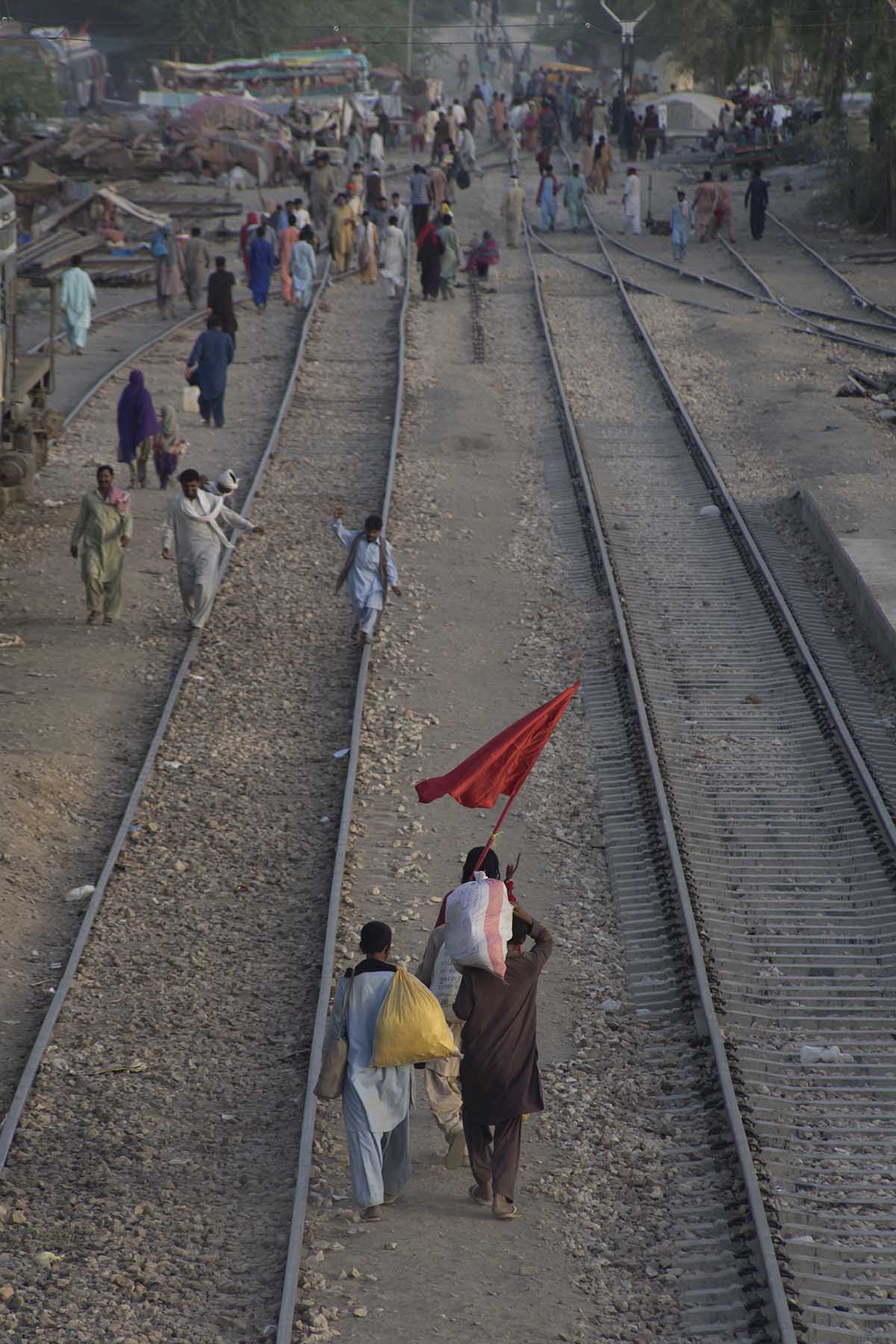

Sehwan’s little train station had morphed into a carnival-like campground on the eve of the saint’s 767th urs. Rolled out reed mats filled the platform, bodies spread on the stairs up and over the old iron bridge, filling the next platform too. Many were sleeping, some with their whole families packed tightly around them. We tiptoed around pilgrims to reach the small station.

A hashish cloud rose up from a cluster of long-haired malangs, vagabond Sufis who hop from shrine to shrine on long-haul, full-bodied quests to find God. One sat shoulders tall, alert as he smashed a ball of bhang in a mortar. Another leaned back against a big burlap sack, eyes wild, glowing red, perhaps reflecting the fairy lights beyond.

There to greet us at the station was a friendly-faced, barrel of a man named Zulfiqar, a railway officer at Sehwan. Through a friend in Karachi, he’d been tasked with escorting our party (myself and two Danes) through Sehwan for the festival. Nudging an elbow into my ribs as he pointed to the band of malangs, he explained that such drugs are illegal. Here, however, on the outskirts of town, authorities turn a blind eye, or at least they do for the duration of the urs.

Faint webs of red and green fairy lights speckled the blackness beyond the chaotic station, hinting of a sea of tents stretching northward, where the lights of town glimmered brighter. Off to the sides, trails of slow-moving headlights flickered on the horizon, likely buses moving on the highway, loaded with pilgrims and blaring their horns, trumpeting their late arrival.

Past the station, scattered drums rumbled too. The urs would begin the next day, but the party had already started.

The Royal Red Falcon

High among Pakistan’s preeminent Sufi saints is Sayyid Usman al-Marwandi (1177–1274). Likely born near Tabriz, right in the path of approaching Mongols from the east, he traveled in ascetic style over the course of the early 13th century, racking up impressive mileage for the day. Somewhere between performing his hajj and traveling to Syria, Mashhad, and Baghdad, he joined the Qalandariyya, a ragtag order of celibate wanderers, graveyard sleepers, ‘unruly friends of God.’ By the mid-thirteenth century, he’d arrived in the Punjab, eventually settling in Sindh.

Over his last two decades along the Indus, Lal Shahbaz forged connections for the Qalandariyya with the mainstream orders of the day, teaming up with contemporary spiritual giants to form a quartet of Sufi pioneers: the chahar yar (Persian for ‘Four Friends’). In Multan, it was none other than Bahauddin Zakariya who initiated the wanderer into the Suhrawardiyya. The final two friends were Baba Farid of Pakpattan (of the Chishtiyya) and Jalaluddin Bukhari of Uch Sharif (Jalali Suhrawardiyya).

By the time of his death in Sehwan, al-Marwandi was of course far better known as Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, the ‘Royal Red Falcon,’ so named for his soaring devotion and penchant for dressing in red, his color of choice. Achieving an ecstatic state through combinations of music, dance and drugs, he’s credited with numerous miracles and acts of self-mortification, in classical Indian-style. Among other humiliating rites, he was known to perform tapasiya: sitting right over a cauldron of fire as his skin slowly turned his favorite color.

Among his great devotees are about all of the subsequent saints to arise in Sindh—including Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai, Makhdoom Bilawal and Sachal Sarmast, each with a great urs of his own. Doubtless, Lal Shahbaz’ legacy also helped shaped the beloved Mian Mir, a Sehwan native of the Qadiriyya, and both friend and pir to three generations of Mughal emperors: Jahangir, Shah Jahan and the erudite, mystically inclined Prince Dara Shikoh. His ideals of transcendence, divine oneness (wahdat al-wujud), love and tolerance resound loudly in Sindh to this day.

His shrine and urs draw Sindhis, Balochis, Sunnis, Shiʿa, Ismaʿilis, Suhrawardis, Parsis—even Hindus. For these, Lal Shahbaz has taken different shapes: a 4th-century Shaivite saddhu (one who has renounced the life of this world), or a manifestation of Jhule Lal, Lord of the water and the Indus.

Indeed, as in most other towns across Sindh, a good chunk of Sehwan was comprised of Hindus until Partition. Only a few dozen remain. But as at the very start of tradition surrounding the saint, Hindus still carry out an integral role in festivities. They’re largely in charge of the pre-wedding mehndi (henna) ceremony. In lieu of a typical bride, it’s a chadar (a large, silky, velvet, embroidered cloth) that receives the adornment, heaped with flowers and spread over the tomb of the saint.

I’d arrived in Sehwan with plenty of excitement: over the coming two days, I expected to witness it all for myself.

Approaching the Shrine of the Qalandar

‘Triple bypass,’ Zulfiqar chuckled the next morning, a hand on his chest, It was a surgery he’d had about six years before. Sweat beads bulged on his brow as we waited to cross the dusty highway just north of the chaotic train station, dozens more buses and trucks rolling in from the desert with pilgrims packed on their roofs. Honking rickshaws and Qingqis (motorbike rickshaws) wove in and out between them, invariably overcrowded. Some passengers chanted or waved bright red flags. It seemed everyone was headed in the same direction.

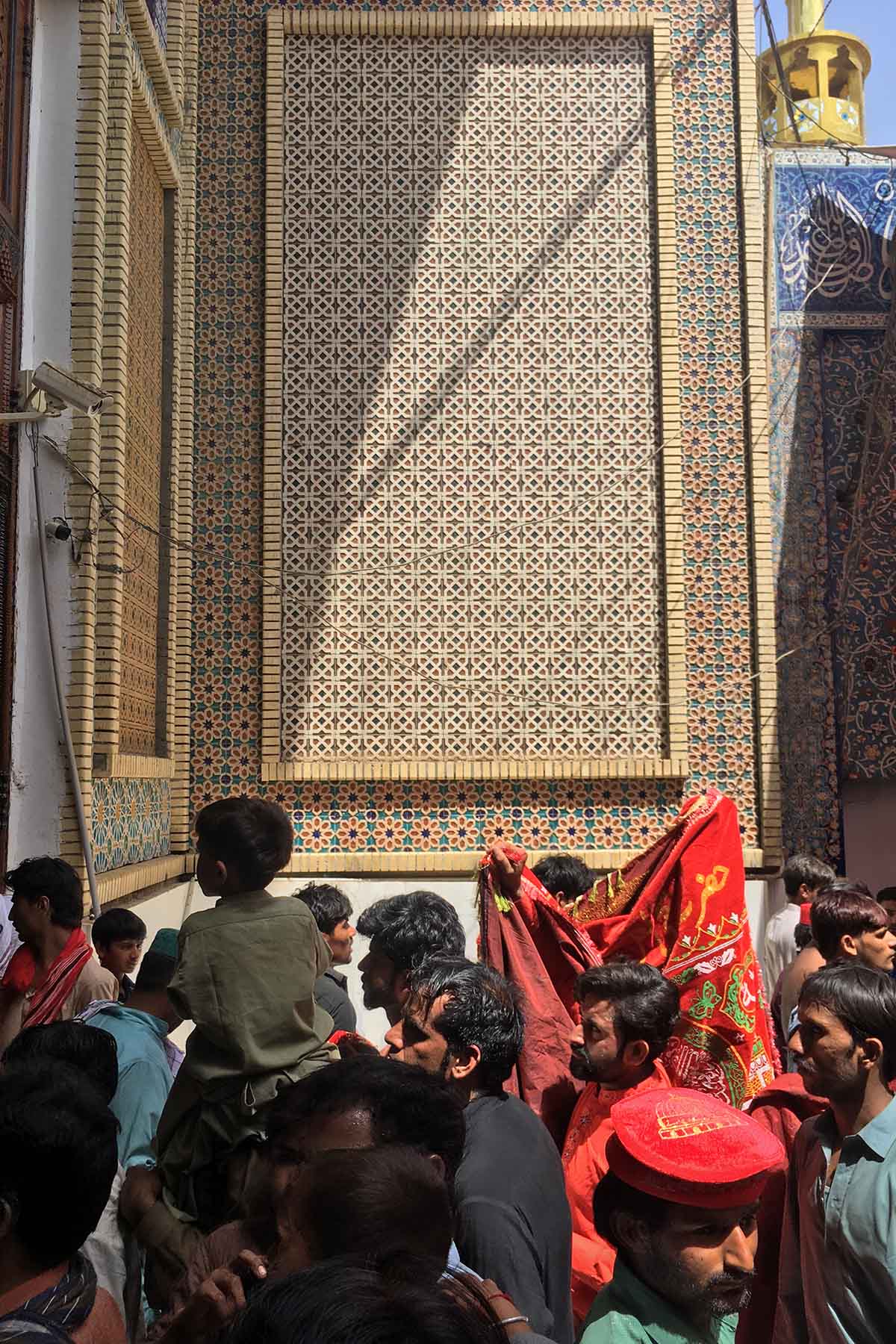

We moved with the crowds past shops piled high with rose petals, sweets, qawwali CDs and golden-framed icons of the saint. A police barricade soon marked the point beyond which only bodies were allowed: a swirl of saris and skullcaps wafting with rosewater, incense and sweat. I guessed over a thousand men and women were crammed within sight along the one, narrow walkway ahead, inching toward the shrine beneath of a palor of dust in an already flattened, nearly-noonday sky.

Glinting up ahead, the first sight of the shrine’s golden dome made my pulse quicken slightly. I guessed that the entrance was only minutes ahead, even in the slow-moving crowd, but another fence soon appeared, a much larger police barricade complete with barbed wire. Quickly spotting our pale, foreign faces, an officer called us over, seemingly hurried. We pushed through the crowd to reach him, producing our passports as instructed. A group of officers soon gathered and looked our documents over, then looked us over. Then they turned to Zulfiqar for a lengthy interrogation.

Terror and Safety in Sehwan

Some 5,000 police officers and 1,000 Rangers were on duty in Sehwan for the urs, keeping an eye on the hundreds of thousands of festival goers—or by some estimates, up to a million.

In the long spate of terror attacks unleashed in recent decades across Pakistan, Sehwan has received its share of attention from those irked by deviance from more rigid iterations of Islam. Most notably, in 2017 the shrine itself was the target of a suicide attack, one that killed 88 pilgrims and injured many more on a typically crowded evening at the shrine. But in a show of defiant courage, the shrine’s keepers and devotees shook the episode off like a passing cloud of dust. The mazar was running again as before within 24 hours, welcoming pilgrims as it had for more than seven hundred years.

From the Islamist perspective, of course, Sehwan’s critics have a point. The whole spectacle most certainly resembles a Hindu mela, from the musical instruments to the accompanying sweets (prasad), and not least the dance (dhamaal), easily seen as a veiled continuation of an ancient dance of Shiva practiced here. Indeed, long predating Islam, Sehwan was a cult center for the Pashupatas, famed for just such a dance! Like Qalandaris, they practiced self-mortification, pursuing their own abasement in the quest for God.

Elsewhere in Pakistan, the hardline, Deobandi distaste for it all prevails: of shrine veneration as heresy, shirk (‘association’ with God), outright idolatry. Over midnight suhur in Islamabad weeks later, my Sunni hosts scoffed at my mention of Sehwan. ‘That isn’t Islam,’ they explained, maybe a but disappointed that I’d become exposed to the faqirs and majzubs of the urs. ‘[Sufism] is not part of our tradition.’ I met with similar distaste in Lahore and Peshawar. But across much of Sindh, the softer, Barelvi school of thought prevails, a good majority welcoming visits to shrines for the veneration of Sufi saints.

Wrapping up with police, our thoroughly Sindhi host Zulfiqar wiped his brow, relieved: we’d have to turn back. It was simply too busy to approach the shrine at the moment. ‘For our safety,’ he said, not specifying from what. Perhaps reading my disappointment, he assured me there’d be plenty of time to go later.

The Shrine of Nadir Ali Shah

For now, Zulfiqar led us into a narrow, covered side street crammed with more shops filled with sugary treats and trinkets, guarded by a man with a snake-charming flute. A pair of hijras (members of Pakistan’s third gender community) brushed past in tight-fitting dresses, followed by a small band of Sufis in matching white kameez, red scarves and notched, Sindhi skullcaps with rasta embroidery, pointedly framing their foreheads in shapes that resembled the tops of mihrabs. Catching sight of my camera, one grinning disciple requested a photo, then pointed to the eldest of the bunch, the one with the white beard. ‘Our murshid (spiritual guide),’ he announced with genuine excitement.

Moments later, an arched gate marked the entrance to what appeared just another of the town’s many shrines. Zulfiqar turned to me, face flushed, to explain that we’d all take rest in the complex for the worst of the heat—and lunch. The main function, it seemed, at this particular complex on this particular day, was the provision of langar: charitable, communal meals. The keepers inside, all wearing the same niche-rimmed, boasted that they’d feed tens of thousands on just that day. The entire operation, they said, runs solely on the basis of charitable contributions. ‘100 percent free.’

We first circled the complex’s shrine, built for one Nadir Ali Shah, a 20th-century ascetic claiming a strand of successorship from the great Qalandar. Led to a tiny sitting room beyond a dreary concrete cattle stable, we squeezed inside, a dozen or so sweaty men, with more arriving. The windowless room became gradually smaller as the curry and goat’s milk were brought out on trays. An old man pressed a pipe to his mouth and a cloud of cannabis smoke billowed. After taking his turn, a much younger man drew far too quickly, collapsing against a wall. Thanking our hosts, we at last stepped carefully around the bodies and into the fresh air of the courtyard, where the young man from earlier was bent against the stables, violently retching.

After a few more stops for tea and rest along the way, we made it back to our humble room by the railway station. Despite the drums, now in swing, booming loudly from all directions, it wasn’t just Zulfiqar that instantly crashed.

Second Approach to the Shrine

Waking in the evening, I was anxious once again to reach the shrine. We hired Qingqi this time, wrapping around to approach from the north. It was Zulfiqar’s idea. Crisscrossing the approach were dozens of creaky buses, some adorned in the style of Pakistan’s world-famous trucks. Crammed along the shores of the tiny lake to the north were hundreds more, the bulk of the pilgrims they carried having already spilled into the town’s narrow alleys beyond.

A dust storm gathered as we reached the edge of the crowd at the base of the old ‘fort’ just north of the town gate. Many sources continue to erroneously link this enormous mound of dirt to Alexander the Great.

While stationed here in ‘Sewistan’ in the 1840s, Richard Burton mocked the same misattribution, playing a practical joke to expose the British obsession with Alexander. He planted a fake ancient pot on the spot, then watched as excitement spread before admitting to his deed. The crumbling fortifications, however, are certainly ancient.

In around 1334, about sixty years after the death of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, the Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta was the first to note the presence of his shrine, but in those days it stood well beyond the town, then still synonymous with the outline of the walls of the fort. Pulled by the growing popularity of the mazar, the town would shift southward over the centuries that followed.

Much like Burton, who complained of Sehwan’s heat and described it as ‘miserable and dilapidated,’ with ‘nausesous odours,’ a ‘miasmatic land,’ Ibn Battuta called it a sweltering, dreary place where locals live poorly: surviving on sorghum, peas and turmeric-stuffed, tailless lizards (which he dared not try).

His major observation here was focused on the action at the ancient fort, where he witnessed a forty-day siege. A powerful Multan qadi (judge) had chosen to hunker down here in a rebellion against Muhammad bin Tughlaq, the Sultan of Delhi (r. 1325–1351). The Sultan’s mamluk, responsible for Sindh, made a deal to break the siege, then swiftly broke it.

What happened next, in the traveler’s own words, is not for the faint of heart:

‘Every day [the Sultan’s mamluk] would strike off the heads of some of them, cut some of them in half, flay others of them alive and fill their skins with straw and hang them on the city wall. The greater part of the wall was covered with these skins fixed on crosses, striking with terror those who saw them. He also collected their heads in the middle of the town where they formed a mound of some size. It was [shortly] after these events that I lodged at a large college in this town. I used to sleep on the roof of the college and when I woke up during the night I would see these skins attached to the crosses; they filled me with horror and I could not bear to stay in the college, so I went elsewhere.

In the faint light of dusk, pilgrims struck silhouettes on the high mound, likely standing atop the ancient wall where the scene above so horrified Ibn Battuta. Then, in a sudden, tsunami-force gust, the figures disappeared completely: a cloud of dirt from the desert sweeping down over the crowd, whipping up the mound in a flurry of tiny dust devils, stirring up plastic trash.

The tumult went almost ignored by the bulk of the crowd, simply shuffling along after covering their faces with scarves. As the fury subsided, the sound of drums returned, beating faintly ahead down invisible alleys. The cheers sounded louder, echoed down the line. Inching onward, we passed beneath the town’s northern gate, feeling hyped—by the cheers, perhaps—for what awaited beyond.

But once again, it wasn’t to be. The near deadlock convinced a weary Zulfiqar, who then convinced me (at some length) that it was best to wait a few hours more (he knew a place) before making our push to the shrine.

As the evening before, we turned down a side street, arriving in a small, private courtyard of a friend of a friend. Tea was served and biryani brought out. We thanked our gracious, though antsy to move. At last, when I suggested we do so, our magnanimous host protested: it was now getting late. All were tired. Zulfiqar touched his chest, mentioning again the surgery. ‘Triple by-pass,’ he sighed. When the rest stop was over at lat, we were lead right back through the northern gate.

Dhamaal: A Dance to the Center

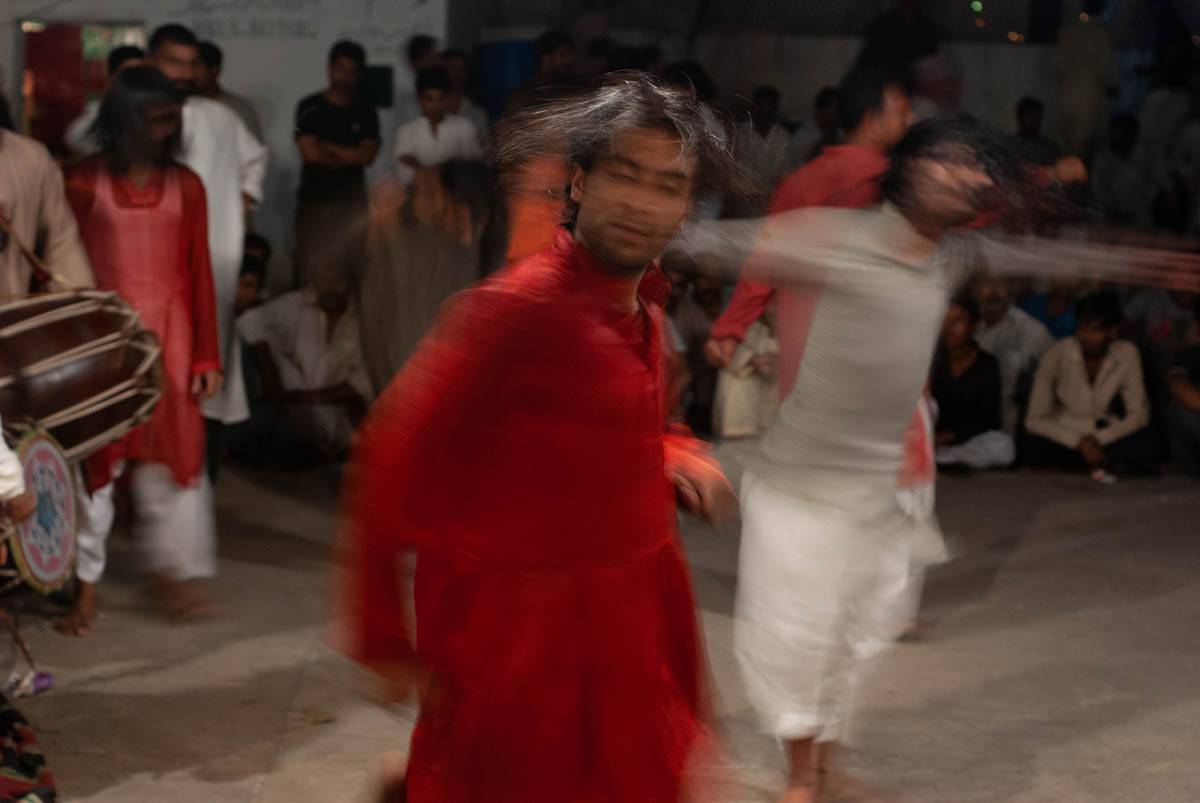

Back at the camps outside the railway station, troupes of drummer had kicked the night into full gear. The crowds were much larger and packed tighter than before. It seemed all had arrived. Like festival stages, circles had formed around various bands with those at the far edges swaying in measured fashion while those a bit closer to the center whirled, stomped and flailed more freely, reminding me of the Sufis dancing the night away at Lahore’s Shrine of Baba Shah Jamal.

A whole decade ago, fresh from a journey along the Grand Trunk Road and exhilarated at my very first day in Pakistan, I’d stayed until 4am with a ragtag group from Lahore Backpackers (where everyone carrying the Lonely Planet wound up). Incredibly, one of the percussionists at the shrine was deaf, keeping the rhythm through sheer vibrations felt on his belly. Together, they spun for what felt like hours, leaning far back against the weight of their drums, their bodies blurring into circles of red—also the color of their saint.

They were dancing dhamaal, a sacred ritual with murky origins in which dancers often aim to transcend themselves. As well as having at least possible links to the dance of Shiva performed here in pre-Sufi days, the ritual likely owes something to Siddis—Afro-Indians, largely brought to the Subcontinent as slaves.

Pressing forward for a slightly better view of the action outside the railway station, I found myself pushed to the inner edge of the ring, then shoved even further, to the center. A man grabbed my hand, then raised it, pumped it, bringing to mind a rave. Trying to forget the unwanted image, I made my best effort (a poor one, for sure) to blend into the inner circle’s dancers, mimicking the dancer to my right, at least until he closed his eyes for a long moment to suddenly erupt in shaking. It was a step too far. Imagining half the crowd’s eyes fixed on me, the flat-footed foreigner, I felt a touch of the mortification and loss of pride so sought by Qalandaris, but little of the pious satisfaction. I slunk from the circle as soon as I could, my heart pounding.

The drums boomed on all night.

The following day would be our last in Sehwan Sharif.

The Pilgrim’s Route: Further Indus Shrines

About a week earlier, I’d landed in Karachi, where I visited another celebrated Sufi shrine, in honor of another of Sindh’s foundational saints and awliya’ (friends of God): Hazrat Syed Abdullah Shah Ghazi. The tomb of this 8th-century saint is raised on an ancient hillock just back from Clifton Beach. Little more than a hut until a century ago, the tomb was embellished by Syed Nadir Ali Shah, the same Qalandari whose complex in Sehwan provided us lunch on our first day (naturally, there’s langar on offer here too). After a terror attack in 2010, renovations again revised the look of the shrine, now a spacious, gleaming, Kashi-tiled complex with wonderful views of the City of Lights.

One theory has Karachi’s great saint marching right next to Muhammad bin Qasim, commander of the first Muslim army to saw off a piece of the Subcontinent—way back in Umayyad times. It’s arguably Karachi’s most sacred spot, and many pilgrims in Sehwan would have paused here as well on their route. The more shrines reached the better, it seems, isn’t only my approach in travel planning; most pilgrims hit several, with Lal Shahbaz Qalandar’s tomb as the climax.

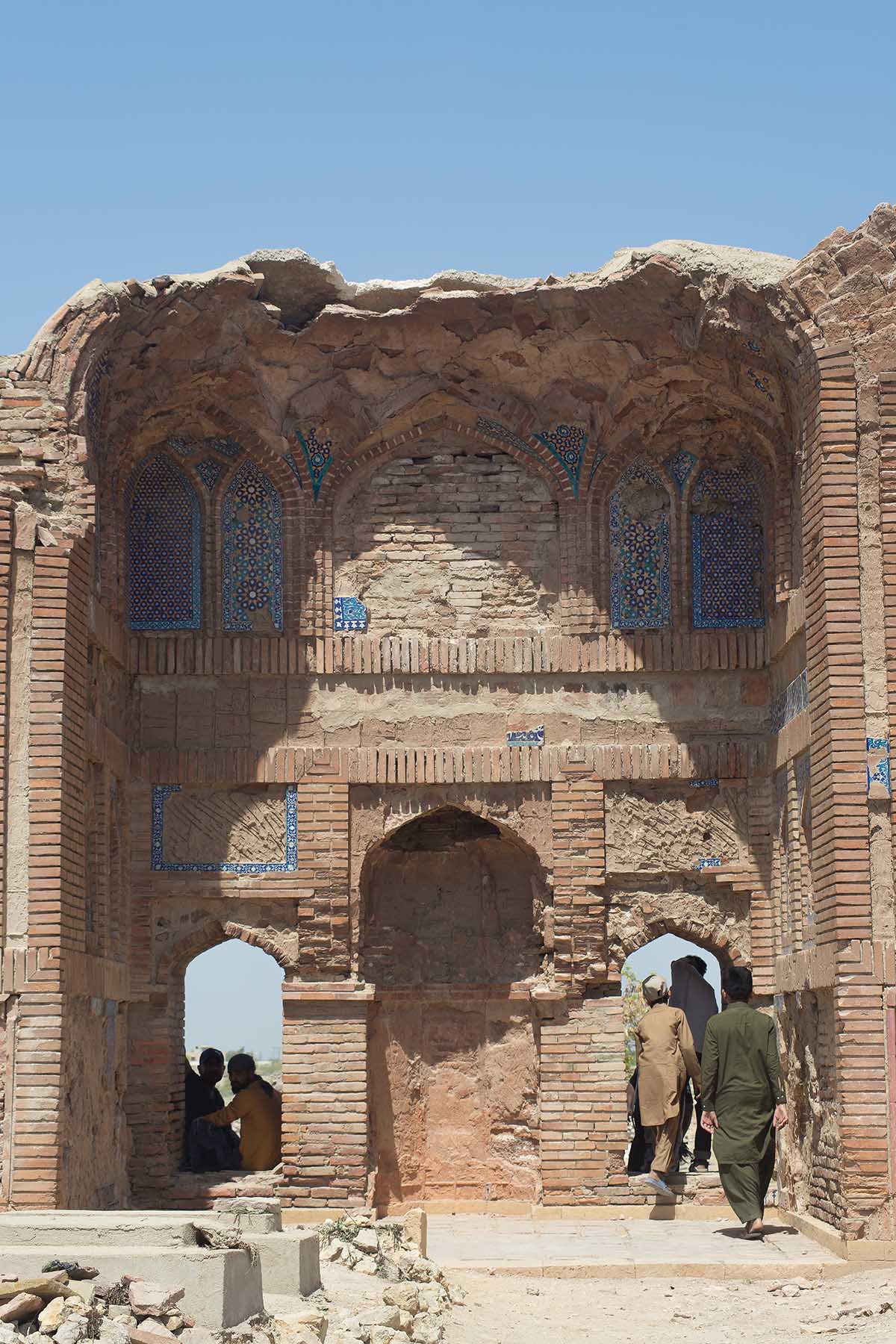

Just a few days before the urs in Sehwan, I’d also stumbled into a smaller urs in Makli, a couple hours’ drive from Karachi: at the shrine of Syed Abdullah Shah Ashabi. Believed to have landed in Sindh from Baghdad in the 10th-century, his complex borders Makli’s famously vast necropolis. With the timing of the three-day festival there, just north of Sindh’s medieval capital, Thatta, many pilgrims among the crowds at Makli’s complex would soon, like me, head north.

neSehwan’s Second Shrine: The Shrine of Bodla Bahar

In Sehwan itself, a pilgrim’s route to the mazar includes further stops at secondary shrines, speckled like satellites around the Red Falcon’s. Besides the saint’s, the most famous of Sehwan’s mausolea honors Bodla Bahar, the Red Falcon’s most beloved Hindu disciple. According to the legend, he was cut into pieces (more than once) by the local ruler for the crime of annoyingly repeating the name of the Qalandar, who—just after each instance of thorough dismemberment—again called his disciple’s name to miraculously reunite his parts, returning him to life.

Bodla’s tomb was only steps past the point that we’d reached on the night just before, again following the wafting incense and the streaming crowd as it inched its way southward from the fort.

Along the railing beside the petal-smothered complex, a smattering of pictures depicted the faithful, long-bearded disciple beside the Qalandar. The Master brought to mind Jesus in the way he embraced his disciple against his chest or, in other images, clasped his hands together like Christ in Gethsemane, pleading to the Father to let this cup pass.

Third (and Final) Attempt at the Shrine

Rejoining the tight, covered alley with the throng, I could almost feel the golden dome of the mazar getting closer. Zulfiqar led the way, huffing in the heat. I almost flinched when he turned to face me, weary. We’d all take a rest stop ahead. Don’t worry, he assured, we’d make it to the shrine just after. It was only right around the corner. To Zulfiqar’s point, the dome then almost immediately appeared over a barbed wire fence, within throwing distance. Also to his point, it truly was sweltering that afternoon.

We climbed to the first floor of a cafe without walls, only floors held up by half-finished columns, allowing for views across the road to the east, where the barbed-wire barrier still obstructed about half of the shrine.

Just as the tea arrived so did a deep-sounding dirge, rumbling somewhere from the west. A parade of bare-chested men then approached, soon passing directly beneath where we sat. They all followed closely behind a ceremonial casket adorned with the silver standard of South Asian Shiʿa: the panja, or upright hand.

Then each man raised his arm, keeping the sad song alive, and in near perfect unison with the rest, let it fall with great force and a nauseating smack against his chest. Then again, and again, and again in the ritual of matam (self-flagellation). With each strike, the deep thump seemed to silence all else along the chaotic street. Sweat flew like sparks between bodies, glinting in the sun, as the skin grew redder and more raw.

I gasped when at last I noticed the scars: deep and crisscrossed, blazoned right across the men’s backs, accrued over previous commemorations of ʿAshura: the tenth of the month of Muharram, when the Shiʿa solemnly and viscerally recall the martrydom of their beloved Hussayn. In Sehwan, the matam crowd had only emerged as a part of Sehwan’s vivid mix (with official Waqf recognition) since the 1980s, most arriving from Punjab. In 2011, they’d supposedly even been allowed to build fires in the shrine’s courtyard, used to sharpen their blades. The blades, I knew, were sometimes part of the ritual, a part I hoped they’d skip today.

Against the backdrop of Sehwan’s older tradition of swirling harmony and fusion, of its anti-sectarian message of transcendent love, this parade of mourners felt jarring. Zulfiqar too, I noticed, was wincing at the scene interminably unfolding on the street.

At last, the thumping went still and the clamoring of the crowd swelled back to the regular din of the urs, the bare-chested posse soon joining the crush at the entrance to the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar.

When the tea was paid, Zulfiqar sighed and gave me the nod: it was time.

At Last: the Qaladar’s Shrine!

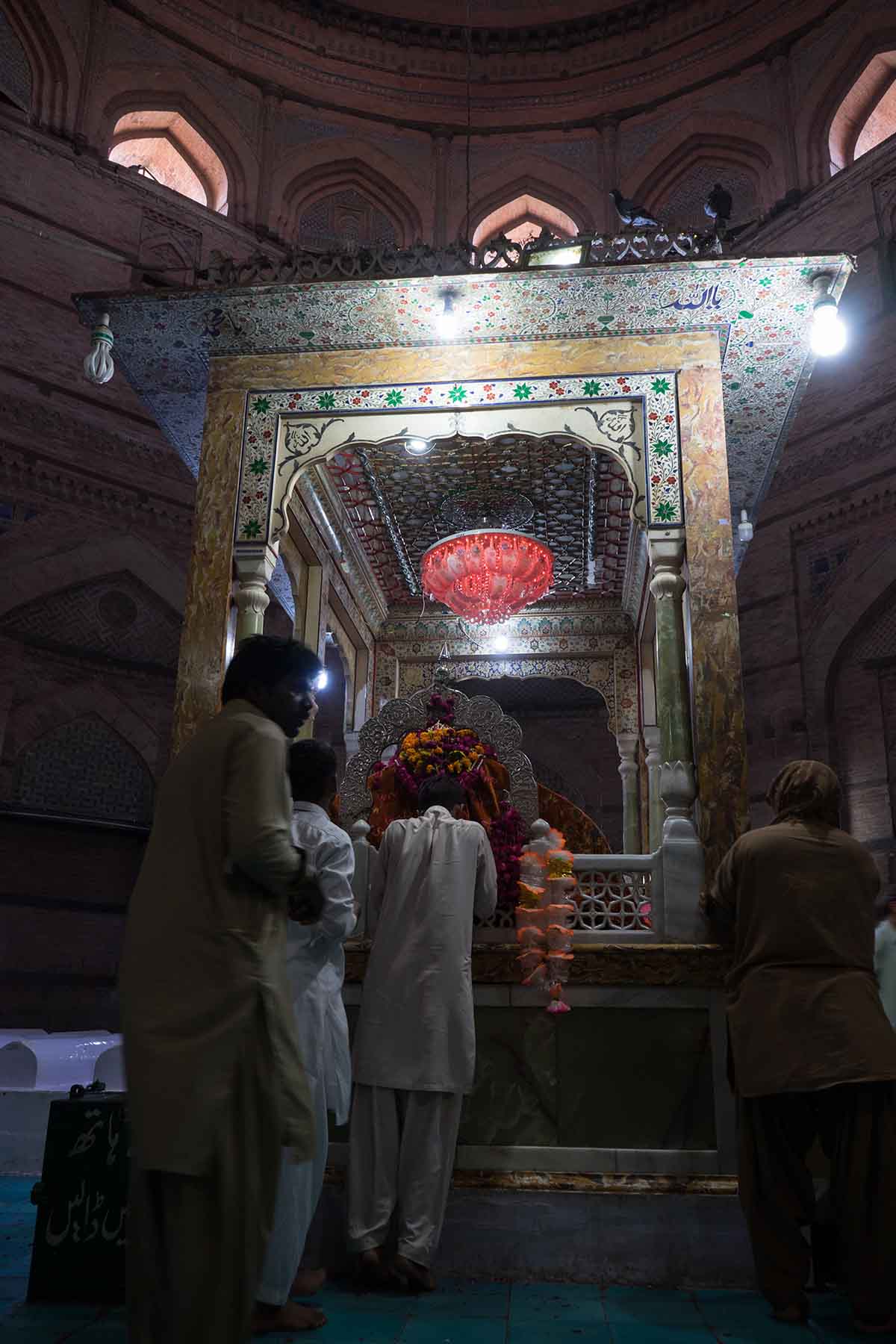

A few minutes later, we were facing the portal to the shrine. Though a shrine on the spot was established, as mentioned, by the arrival of Ibn Battuta in the 14th century, its beautification really got underway some four hundred years later, restored and expanded in the 1970s under the tenure of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, then again under that of his daughter Benazir. After the terror attack of 2017, the dome was given another facelift and the floor inside fixed.

I’d seen pictures of its beautiful kashi tiles online, but today it was just about wholly obstructed: a pair of security gates and corrals with metal detectors were spread up to the wall.

Leaving sandals with the apparently overwhelmed keeper of shoes by the side of the road, we pressed into the queue, where sporadic shouts rose up–of ʿAli! and dam dam mast qalandar! Perhaps overexcited, some men climbed the railing to stand high above the crowd. Their shouts were most often echoed down the lines, keeping spirits high despite the heat and delay.

No cameras were allowed past the gate, where it seemed for a frightful moment that our American and Danish passports—far from helping things along—might keep us from entering at all. The ranking officer here demanded some proof that our visit was in line with Pakistan’s tourist ‘protocol,’ a laborious system by which foreigners have at times been obliged to travel with a security detail. Zulfiqar’s help proved vital in the moment. Standing up straight with his broad shoulders wide, he convinced the officers that he was security enough. The mood lifted, and mobile photos with the officers followed by request. Let past, we at last stepped into the brilliant white courtyard of the shrine, its floor burning our feet, urging us onward.

The space beyond the wall offered a moment’s respite, large patches of the marble floor bare. Across the courtyard, however, in the steaming corridor, pilgrims were again packed together, each vying for space in the approach to the gilded doors of the shrine. Mostly men—but a few brave women as well—pushed their way into the inner sanctum to circle the tomb. Others stumbled back out in a daze. As a dreadlocked malang in shiny red garb slipped out, I noticed more speckles and smears of red, glinting on shoulders, backs: blood, rubbed off the open wounds of the shirtless Shiʿi parade. So the blades had come out. Some fresh wounds they’d inflicted against themselves had soaked right through the scarves some had draped over their backs.

Shiʿi women, huddled off to the side, shouted out their own chants in unison, beating their chests as well, and, it appeared, with just as much force as the Shiʿi men.

At the threshold of the shrine itself, the deep, somber thumping faded, replaced with the echoing tussle of bodies and frenzied shouts from inside the cavernous mausoleum. The portal was almost overhead. Beyond it, a dense circle of pilgrims, pulled into a single mass around the tomb of the saint. A man had somehow climbed his way up over the crowd to stretch a hand through the jali (latticed screen) in an attempt to graze the saint’s chadar. A moment later he was gone, swallowed back into the whirlpool.

As I braced myself at what appeared the point of no return, a firm hand grabbed my shoulder.

Zulfiqar’s eyes were bulging: it was time to turn back. It was too much to join the maelstrom just now.

There was a part me tempted to defy him, to take just a couple more steps and be sucked inside. I’d at last come this far, only to barely glimpse the mazar of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar – and at the height of his urs! You’ll return when it’s quieter, he’d suggest, when the urs is over, you’ll come back. Perhaps I will, I told him, God willing. But at Zulfiqar’s hand on my shoulder, right on the cusp of reaching the shrine that had taken days and multiple attempts to finally reach, I was mostly just relieved.