A truncated version of this story was published on BBC Travel in November 2022.

The approach to Egypt’s Church of the Blessed Virgin atop Jabal al-Tayr (the Mountain of Birds), roughly 250km south of Cairo, once involved a perilous, vertical scramble up a cliff rising straight from the Nile. Only close to the top began the series of steep, rock-hewn steps, still visible through today’s iron fence by the ledge, which brought you to the church. In the 19th century, its handful of outside visitors were certainly impressed, stunned not least by the sanctuary’s obviously ancient foundations. One reported that according to the custodians, it was built in the early 4th century on the order of Constantine’s mother Helena. For centuries, its current custodians explained to me, the blessed location has produced untold miracles in Egypt, miracles that continue to this day.

My recent approach to the church was somewhat smoother: in an air-conditioned car along a well-surfaced road. Heading south along the Nile’s east bank past a chiselled, white landscape of quarries dating back to the pharaohs, a cluster of Coptic graves grew more tightly packed as I neared the Mountain of Birds’ sacred core. Past yet another checkpoint, I arrived at last at a neat little car park just opposite the church, its walls freshly plastered and oddly ringed by a fence, like a prized display at a museum. A metal detector now marks the portal to the sanctum and its cave, where it’s believed that the Holy Family—Jesus, Mary and Joseph—stopped to rest on their flight from King Herod’s wrath, as noted in Matthew.

‘Take the young child and his mother and flee into Egypt,’ the angel told Joseph, whose celebrated journey would begin as Abraham’s, ‘not knowing whither he went.’

According to Coptic Christian tradition, based on alleged holy visions and local lore, the family’s route would wind west from Bethlehem to Egypt’s Delta before doubling back, then hopping from bank to bank, eventually reaching deep into Upper Egypt, even beyond Jabal al-Tayr. Marked with many dozens of miracles, their momentous, round-trip journey racked up more than 3,000km.

In a bid to bolster “spiritual tourism” and spotlight the country’s Christian claim to fame, Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism & Antiquity recently launched the Holy Family Trail, mapping out some 25 stops along the route. Naturally, these comprise some of the country’s oldest houses of worship, of which the Church of the Blessed Virgin—and the sacred cave it was built to contain—is just one. In partnership with the various dioceses and other interested foundations, it’s been busy of late: enhancing a growing list of sites with landscaping, lighting and signage; improving the access roads; and developing accommodations en route.

With some changes substantial and others cosmetic, the Ministry’s vision is far from complete. Nevertheless, word of the Holy Family Trail is trickling out.

In October 2022, starting from the Delta, I set out to trace its southward route.

The Nile Delta

After following Egypt’s Mediterranean coast from the city of Rafah to the classical port of Pelusium (once marking the Delta’s eastern edge), the route cuts south through ancient Bubastis, where the Family’s reception was less than friendly. The infant’s presence is said to have shaken the temples’ foundations, smashing their gods supposed fulfilment of the words of Isaiah: ‘The idols of Egypt will be shaken by his presence…’

When fleeing from the locals’ fury, Jesus then caused a spring to burst forth to quench the trio’s thirst. A well believed to have been built on the site is now ringed with a fence to keep pilgrims from drinking its water.

The family received a warmer welcome on the outskirts of modern Cairo in Mostorod, a town now swallowed by the city’s sprawl. I stopped at the 12th-Century church that was built to enclose al-Mahamah (the place of bathing), another well from which the family is thought to have drunk and washed. The chapel was abuzz, dozens of cameras aimed a similar number of just-baptized babies. To the left, another group stood more reverent, circling tightly around the old well, some scribbling prayerful notes to be stuffed into the sacred grotto.

Doubling back to the north towards Alexandria, the route reaches the towns of Sammanoud and Sakha, the historic churches of which saw restorations declared complete in 2021.

I caught up with the family’s trail at its next major stop, at the fringes of the desert in Wadi El Natrun–the site of a monastic explosion that once filled this desert with aspiring hermits. Dozens of monasteries dotted this stretch, the earliest tracing back to the early 4th century.

Four survive. Of these, three have seen renovations in recent years, among these the careful uncovering of Al-Sourian monastery’s stunning medieval frescoes of Jesus’ life. Before taking leave, the young Jesus is believed to have called forth yet another spring here.

Cairo

After fanning the Delta, the trail circles back to the outskirts of Cairo at Shagaret Maryam (Mary’s Tree), a twisted old sycamore said to have offered the Holy Family shade. Upon ducking through the gate, it appeared I was on hot on the trail of the Ministry’s Holy Family Trail. The entire complex had received a fresh coat of paint, the walls now adorned with the same somewhat foklsy reliefs seen at sites of “spiritual tourism” elsewhere: the trio en route by the pyramids in one, Herod’s slaughter of babies in another. Yet another holy well was glistening too, freshly plastered and steps away from an inaugural plaque, installed just within the last week.

Further along, the agonised

trunk of the oldest tree present stands propped with the aid of supports, beside it a pair of more lively descendants, all ringed by a low picket fence: erected to guard against pilgrims’ temptation to peel its bark or pluck its leaves as souvenirs.

Alighting at the Mar Girgis metro stop, I arrived at the route’s next station, Coptic Cairo, where around the corner from Roman Babylon’s Hanging Church is the Church of Abu Serga, built in the 4th century over the sacred cave that sheltered the trio. Due to the length of their stay in Old Cairo, it’s considered one of the holiest spots on the trail, and more than anywhere else, the approach to the church is stacked with stalls overflowing with Mary merch. Inside, the well from which Jesus and Mary drank, and the stones on which they walked and slept, are protected by glass, neatly labelled in Arabic and English for the crowds headed down to the crypt—where the Family is believed to have rested for three whole months.

I reached the family’s last Cairo stop after a sweaty walk through today’s leafy, upscale district of Maadi. The Family is believed to have used the same steps that connect the Church of the Virgin Mary to the Nile, where they boarded a papyrus boat and sailed toward the ancient city of Memphis and Al-Bahnasa, the latter the site of another future monastic hub.

The old steps to the river were barred by an iron gate when I arrived, a police boat docked nearby. Inside, along with icons of the Holy Family, I admired a glass-encased relic from a much later date: a water-worn Bible plucked from the Nile near the sacred steps in 1976, its pages miraculously open to Isaiah 19:25: “Blessed be Egypt my people…”

Hours later, I was speeding to the south on a train from Cairo’s Ramses Station, unaware that from here on out I’d no longer be traveling alone.

Muhafazat al-Minya (Middle Egypt)

At the junction of Lower and Upper Egypt, the Holy Family cross the Nile from Samalut to arrive at Jabal al-Tayr, now home to the Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Security concerns and long closures in the surrounding region have seen it scrubbed from the map since the 1990s, with tourists most often whisked right past it on trains between Luxor and Cairo. Now open for a decade, this stretch of the Nile south of Cairo has been dubbed a key focus for the ©Holy Family Trail. It’s hoped that the region’s slew of old churches will compound the allure of its rarely-seen temples and tombs.

Upon stepping off the train, it was clear that old security concerns had yet to fade. In line with the protocol for all foreign guests, police would insist on keeping me company for the remainder of the route through the governorates of Minya and Asyut (only finally leaving me free to wander in Qena).

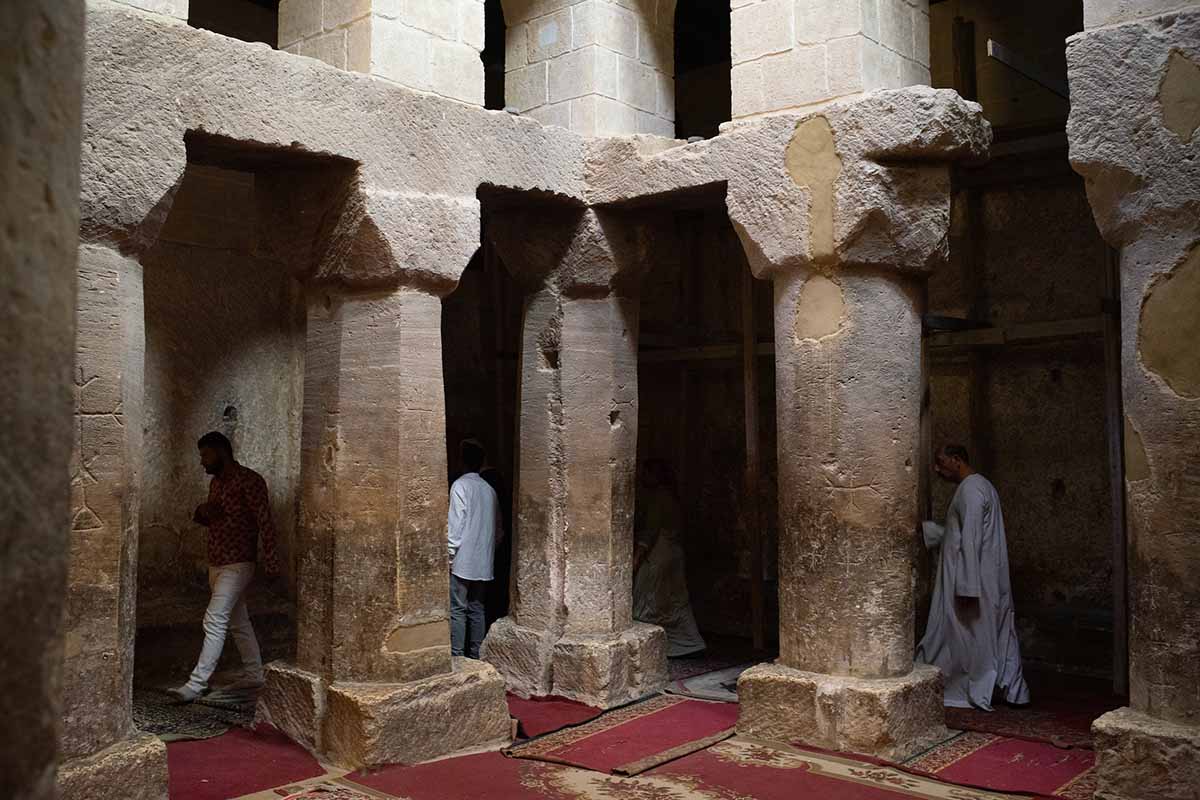

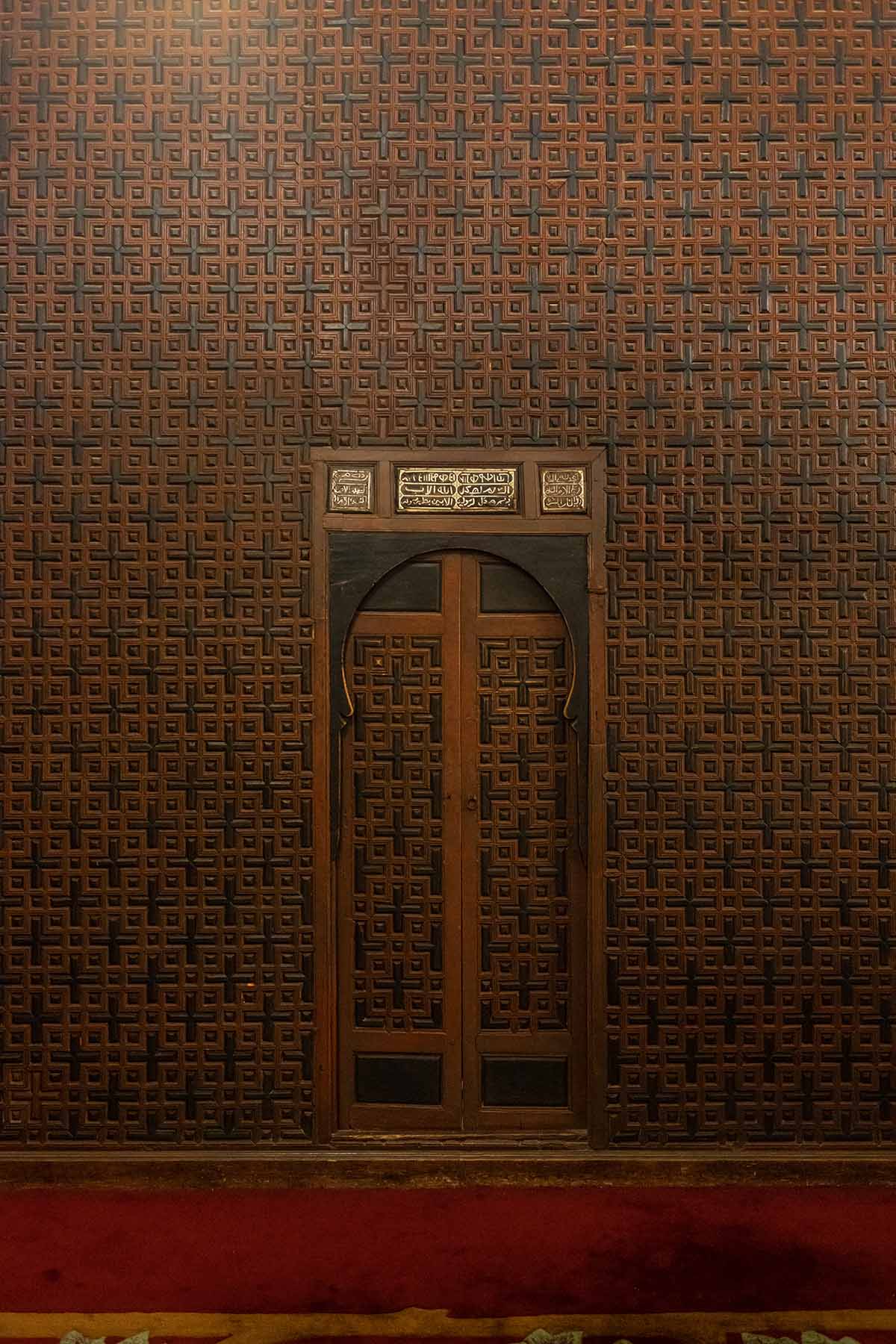

Just steps from the polished Holy Family Hotel, I slipped off my shoes to enter the Church of the Blessed Virgin, where the enormous, rough-hewn pillars of the nave immediately caught my eye. They’re quite clearly centuries older than the basilica-style church. Once smothered with soot, they’re now mostly scrubbed clean, each etched with a stout Coptic cross. Out of one of the massive columns an entire baptismal font was carved at some point, fed with water from the nearby shaft that was only recently uncovered (then covered again with protective glass) once having served as the entry to a cluster of Roman tombs, built in a distinctly Egyptian (and much older) style. A pair of Corinthian columns bounds the steps to the altar, while the ceiling over the nave now soars, having been raised high above the former, one-storey roof of palm leaves that was here about a century ago.

From somewhere behind the church’s iconostasis came the sharp buzz of sandblasters, a cloud of fine dust seeping through the cracks in the wood, rising to the ceiling. Renovations, it appeared, weren’t quite finished.

Beneath the last stretch of scaffolding still to be taken down, I sat on a stone bench in the corner, watching the ebb and flow of pilgrims as they entered the church in noisy bursts, most having just stepped off tour buses parked in the new lot outside. When passing the altar, almost everyone paused to touch or kiss the curtain draped over its doorway. And before taking leave, almost everyone bowed at the tiny cave where Jesus and Mary took shelter. The haze of dust that now filled the nave only added to the sanctuary’s mystical allure.

I peered into the tiny cave myself, less adorned than expected and even smaller than most I’d yet seen. At the back stood an icon of Mary and Jesus propped on a small wooden stand; beside it was a large metal padlocked box with a slot for pilgrims to submit their offerings.

I was lucky to catch the chief engineer on break, having popped through a door in the iconostasis. Very kindly, he offered a tour—just one day after the American Ambassador had paid his respects, he noted. We first stepped through a doorway at the western end of the church, where clutter and tools half-obscured another door, this one capped with a breathtaking pediment of elaborately carved stone blocks, assembled like a puzzle of only lost pieces.

Thanks to repeated ransackings and renovations, the engineer explained, the church had been rearranged countless times, though he noted that no less than seven apostles appeared at the top of the doorway (still a majority of the Twelve).

Echoing others I’d met, he explained that many “miracles” over the years have arisen from this place: from healings to heavenly visions to the answering of all manner of faithful appeals: for pregnancies, promotions, even the curbing of nagging doubts that miracles indeed occur.

After leaving the cave at Jabal al-Tayr, the Holy Family crossed the Nile and continued southward. They eventually reached ancient Hermopolis, now a vast field of rubble encircled by the scruffy town of Al-Ashmonein. Jesus’ miracles here, including the toppling of more temples, are described in the oldest surviving text on the family’s flight, A History of the Monks in Egypt, an anonymous account of the 4th-Century travels of trailblazing pilgrims.

Only on rarer maps of the Family’s route had I noticed a certain extra crossing, landing the trio in one Egypt’s remotest corners, a town still nearly entirely Coptic today.

My police escort (required in these parts) gently tried to persuade me to head somewhere else. Abu Hinis has and surrounds have seen their fair share of the sectarian violence that has marred Middle Egypt for decades. When authorities tried—more than once—to change the town’s Christian name (to Wadi al-Naʿnaʿ), villagers here fiercely resisted in order to keep its cherished reference: to Saint Yohannes the Short.

Upon stepping through the complex’s gate, I stood in the shadow of new and towering buildings, dwarfing the relatively tiny church, its small, weathered bell tower a scaffolded mess.

My heart sank. At other sites of ongoing, state-led restorations I’d learned that closure was the rule.

I was relieved when the Father explained that the renovations ongoing were privately funded. Widescale Ministry efforts at funding and promoting the Holy Family Trail hadn’t touched Abu Hinis. They were alone, it seemed, and had only just started on their own renovations. They appeared badly needed.

The inside was open, the Father assured me. I was further relieved when he added, with a hint of regret, that the ancient church interior’s restoration had yet to begin.

Muhafazat Asyut (Upper Egypt)

Traversing the ruins of Tel Amarna and finding shade at Dayrout al-Sharif, the Family infuriated a few more pagan priests before finally reaching Mount Qusqam. Roughly 300km south of Cairo, the stop is the trail’s most hallowed. Encompassed by the fortress-like Deir al-Muharraq, it’s held by Copts as a sort of Second Bethlehem, having hosted the Holy Family the longest: six months in all.

Past the monastery’s giant gates, a monk who’d spent over a decade in England (and decided it wasn’t for him) led me straight to the oldest church, pointing at a patch of the carpet by the iconostasis: another of Jesus’ miraculous wells, he explained, extended almost just beneath our feet. “We usually say that it ran out of water, but in truth it was buried”—purportedly by Mamluk authorities, intent on stemming the flow of miracles emanating from here. Such such miracles, the monk assured me, repeating a now familiar line, are still seen to this day.

It was here at Al-Muharraq too that Theophilus, Alexandria’s 23rd Pope at the turn of the 5th century, saw a light far brighter than the sun, then the Virgin Mary herself. Theophilus’ vision offered a backbone for today’s roughly 25-station route, his own map expanding perhaps on earlier folklore that had emerged from Hermopolis to the north

When I asked the monk about the giant monastery still further south (and with a rival claim as the Family’s last stop) the monk sighed. ‘That may be what they say in Drunka, but according to history—’ He shook his head no.

For the drive to Drunka, I tagged along with the required police detachment, riding in the back of four separate trucks, some riddled with holes that were less than assuring (though likely decades old).

The monastery complex here was the largest I’d seen along the entire route, stretching up a mountain near the city of Asyut with plenty of new construction underway. Speaking excitedly of various modern-day miracles and ‘public apparitions,’ a nun my age led the way to Drunka’s caves, explaining that one had housed Joseph and the other the Virgin Mary and Jesus. She explained, while pointing into Joseph’s, that in 1986 the Virgin appeared right here—”to confirm to us the truth” of the Coptic Christian tradition’s claims.

Like the line between chronicled history and myth, the exactness of the route is murky. Even the Ministry’s announcements have varied regarding the stops, their number and even their order, reflecting the challenge of dealing with multiple accounts from so many centuries past.

One thing that’s for certain is that the Holy Family’s story continues to intrigue and inspire. And now, the sacred sites that dot their celebrated route are easier to visit, thanks in part to broad-based efforts to develop the Holy Family Trail. As for whether the Ministry’s vision will be realized, that remains to be seen: the trail has yet to lure the desired busloads of visitors from abroad. In Egypt, however, the efforts have already served to bolster local pride, illuminating the country’s oldest faith traditions—one viscerally linking the “miracles” of scripture to the Nile.

In Theophilus’ vision back at al-Muharraq, an angel at last told Joseph that Herod was dead. It was safe to return down the Nile.

When ready, I too headed north on an afternoon train, my assigned officer nearby and then vanishing somewhere in the approach to Cairo, where I arrived with stacks of Holy Trail merch.

Half a century on from the flight, Saint Mark is believed to have followed the Family’s footsteps east to the Delta, arriving in Alexandria to spark one of the world’s oldest Christian traditions. As would be seen, the era of miracles here had only begun.