Before even touching down in Amman, there it was, a stone’s throw from the runway, the first on my list of Jordan’s ‘desert castles’ that stud the bare Badia to the east.

But they aren’t really castles. They belong to a motley array of middle-of-nowhere caravanserais, hunting lodges and palatial Umayyad pavilions, all abruptly abandoned and left to the desert for over a millennium. And they’re far from the only genre of Jordan’s castles: Crusader fortresses, Roman castella (often built on Nabatean foundations) and a great string of Ottoman forts to guard pilgrimage routes linking Mecca. While some of these dotted my route, it was the Umayyad-era ‘castles’ that are the focus of this account of an extended ‘castle loop,’ an expansion on the classic day-trip from Amman.

If you’re sitting on the right side of the plane, as I happened to be, Qasr al-Mushatta is the first one you’ll spot, its great triple arches an odd sight past the tarmac’s chain fence, a bland-looking warehouse next door.

Within an hour or so of landing I’d parked by the entrance, finding myself alone in what’s left of this partially rebuilt ‘winter palace.’ Never finished, it was begun by al-Walid II around 744 AD near the end of the Umayyad era. Its outer façade is a blend of styles unique to this strangely liminal period, emerging from the collision of the victorious Arab armies with the last two colossi of the ancient world: Rome (Byzantium) and Persia. The stones here are intricately carved with vines and acanthus leaves, but the bulk of the façade—inscribed with a riot of exotic and mythical beasts—isn’t anywhere near where it was built. It was shipped to Berlin in 1903, a hefty gift from Sultan to Kaiser. For this piece alone, I imagine it would be well worth a visit to the Pergamon Museum (to reopen in 2027).

What remains in situ by the runway, to the right of the entrance (the qibla wall of the mosque), is by contrast devoid of all animal forms, suggesting that even for the Umayyads such imagery wasn’t quite halal. Indeed, it was still early days for Islam, a fact made clearer still at other ‘desert castles’ off the Eastern Desert’s lonely highways.

Along Highway 40

Striking east of Amman, it wasn’t long before all that was left of civilization was Highway 40, slicing through Jordan’s desolate Badia. About 65km along, Qasr Al Kharana is the first real highlight easily accessible from the road, rising conspicuously over the stony desert, the harra, a mirage over the highway. Built in the early 8th century AD, its forbidding walls and towers resemble a fortress, but scholars seem to think its actual purpose was as a place of gathering for the Umayyad elites of Damascus.

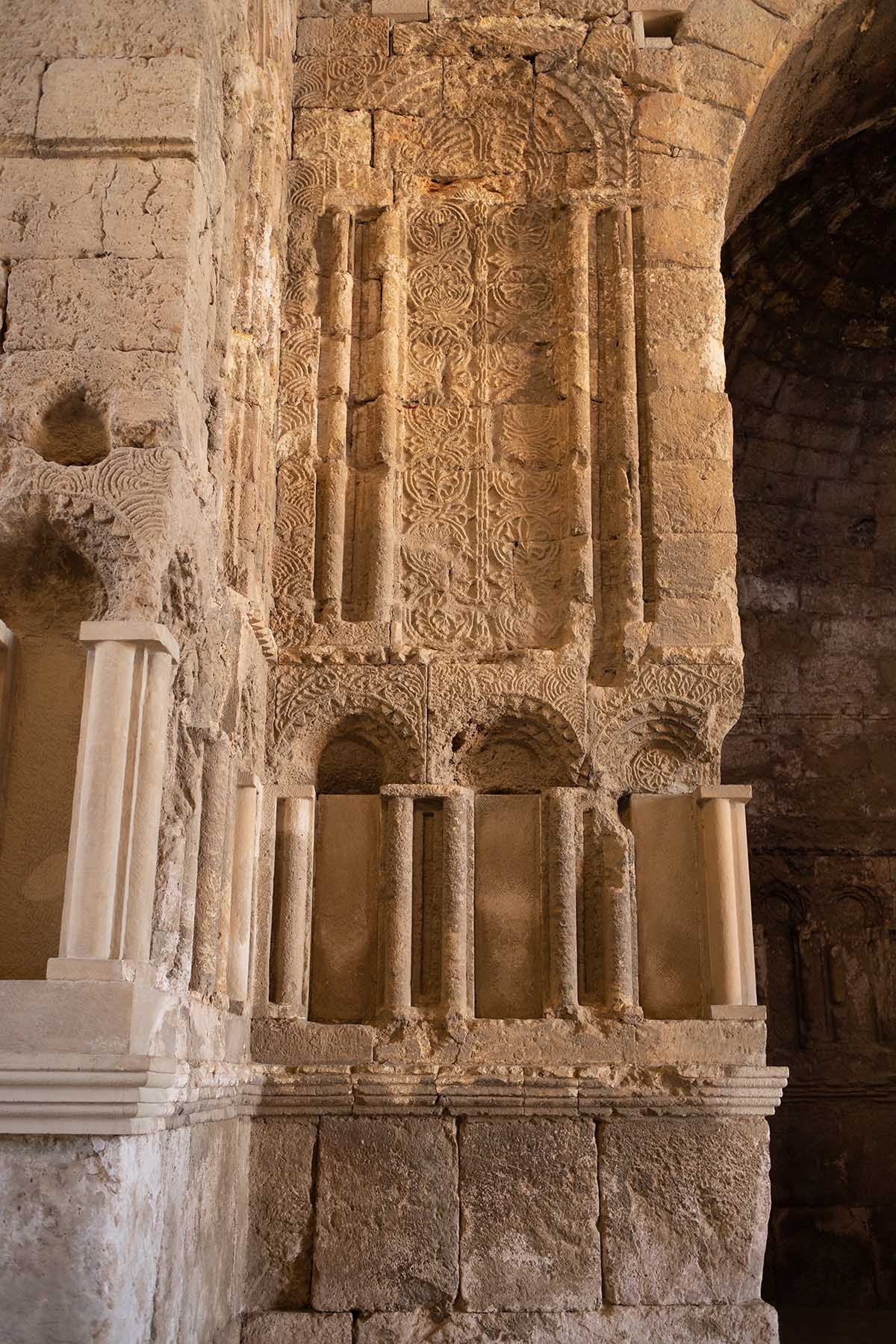

Stepping through the front gate just moments after the only other tourists around took off, the courtyard inside was eerily quiet. I headed up one of the mirrored stairways connecting the upper rooms to admire their vaulted ceilings, triple colonnettes and plaster medallions, again a swirl of ancient styles.

The Bathhouse of Qusayr ‘Amra

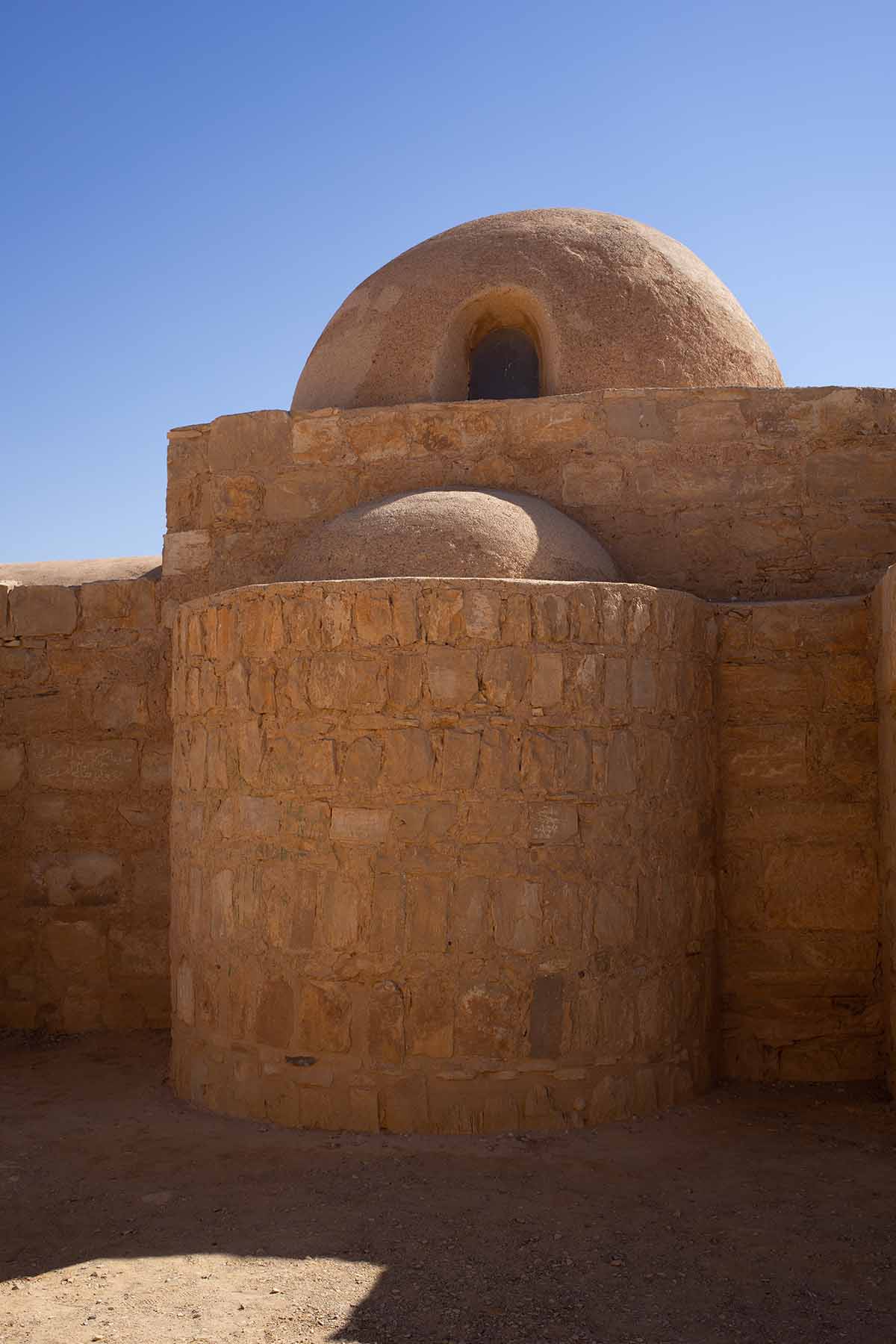

If not for the road sign, 16km west of Al Kharana, I might have missed the turnoff to Qusayr ‘Amra, Jordan’s only UNESCO-listed ‘desert castle,’ rightly famed for its brilliant frescoes. All that’s left of the erstwhile palatial complex is its bathhouse (hence the diminutive name qusayr, ‘little palace’). Its outer stone walls the color of the desert, its quite unassuming from the outside.

It’s generally considered the early 8th century work of Al Walid II, an Umayyad prince who later enjoyed a brief reign as Caliph (743–744 CE) toward the end of the Umayyad era. Grandson of the great Abd al-Malik and son of the hard-line, iconoclastic Al Yazid II, Al Walid II was a lover of poetry, women, wine and the desert. This was one of his several retreats in the Badia, far from the prying eyes of the capital but not too far. Damascus was only several days’ ride through the Badia by camel.

The remote location is much to thank for the survival of the qusayr’s rich frescoes for over a thousand years, first ‘discovered’ in 1898 by the Moravian orientalist Alois Musil. Known in these parts as Sheikh Musa, Musil was entirely bewitched upon passing through. His initial report back home—of a palace decked with fine frescoes of bathing nymphs—was dismissed as beyond belief. He thus made it his mission to document its wonders, returning several times, and at no small risk.

Of course, local Bedouin were familiar with the site long before the chance passing of the increasingly obsessed Musil, but reportedly kept their distance for fear of the jinn said to haunt its interior, manifesting from time to time as owls.

Stepping into the qusayr from the desert, it took a few seconds for the blackened walls to brighten, revealing a rare and evocative glimpse into life in the Umayyad court, a largely forgotten, early Islamic era still gleaming in antiquity’s last light. Among its adornments are ancient zodiac signs, scenes of hunting, labor and revelry, with buxom, dancing women bearing grapes and a monkey applauding a bear on a lute.

A Stop in Azraq

Most ‘desert castle’ tours stop off in Azraq before returning to the west along Highway 30. Famed and named for its wetlands, Azraq is home to a sizeable fort—not Umayyad but originally Roman, largely rebuilt in Ayyubid times and, much later, used as a base by T.E. Lawrence.

“Of Azrak, as of Rumm,” the ex-colonel remembered, “one said ‘numen inest.’”

“Both were magically haunted: but whereas Rumm was vast and echoing and God-like, Azrak’s unfathomable silence was steeped in knowledge of wandering poets, champions, lost kingdoms, all the crime and chivalry and dead magnificence of Hira and Ghassan. Each stone or blade of it was radiant with half-memory of the luminous, silky Eden, which had passed so long ago.”

In the century since, the oasis has run dangerously close to total collapse, with over-pumping (water siphoned to Amman) shrinking the wetlands to within a short breath of life. But thanks to the heroic efforts of the RSCN, it’s hung on, albeit in much diminished form. But the primeval sense of the place is still found on a walk through its last stretch of wetlands or in the old castle’s courtyard.

Basing at the RSCN Lodge, I also made several trips further afield before moving on: to the Shaumari Reserve to spot oryx and to Wadi Dahek, a wide, grinning arch of chalky white cliffs by the Saudi border.

To the Baghdad Highway

Rather than tracing the classic “castle loop” to the west along Highway 30, I headed due north, soon passing the hilltop ruins of Qasr Useikhim, one of three forts in Azraq Castle’s constellation: Roman border defenses, picked for their far-reaching views over the harra.

I parked when the road became too rough to drive and walked the last stretch to the fort, crowning a lonely volcanic rise. At the top, amid the piled basalt, one single, delicate arch stands out, framing the desert to the west. It’s a view Gertrude Bell might have stopped to enjoy on her trek from Damascus to Ha’il, in the company of a caravan of guards and guides. Alone at the top, the surrounding stillness and emptiness all around me, on a windless day, was almost crushing.

That sense of devastation was only slightly sapped when I made it back behind the wheel of my rental to start the a/c. Rejoining the highway north, the nothingness marched on and on, only broken by bone-dry, camouflaged wadis and, 30km off the highway to the east, a lonely, sacred pistachio tree, believed by some to have shaded the Prophet.

The black rocky desert that fans past the junction of Safawi has been called the ‘Library of Jordan,’ its vast flatness hiding perhaps millions of inscriptions—from prehistoric pictographs to notes in a laundry list of languages now dead. But I didn’t have time to get out and search the stones, racing onward to reach Ruwaished, the final stop on the drive to the border, halfway to the Euphrates from Amman. I then doubled back to the west for a few kilometres to meet my appointment at the edge of the highway, watching through my windshield as my 4×4 ride appeared on the northern horizon. I’d be driven the last stretch to Burqu, 20km along a sandy muddle of tracks, tracing a necklace of cairns to the Burqu Ecolodge, opened in 2021.

Since then, it’s not all that hard to visit the remotest of Jordan’s ‘desert castles,’ Qasr al-Burqu. I spent a night at the lodge, taking evening and morning walks to the nearby Roman fort. Though later used by the Umayyads, only the scantest of traces remain of this era in the rubble.

Skirting the far side of the lake for reflected views of the qasr‘s partially crumbling tower, I was grateful yet again to have brought my tripod along when a pack of dogs closed in to claim their territory.

Heading back, I next bumped into a visibly exhausted Bedouin goatherd, trudging at the head of a cloud of dust on his return to the family camp, set beside the new lodge. It had been another very long day with his flock (and his stash of bread and oil) in the baking harra.

The Road to Umm al-Jimal

A couple of Bedouin hitchhikers joined me along two different stretches of Highway 10 (The Baghdad Highway), pointing to unapparent wadis where water holes hid amid the stones of the ‘Library of Jordan.’ Carrying on west past Safawi, I veered north again to reach Deir al Kahf (‘The Monastery of the Cave’), near the Syrian border. A a pair of young boys volunteered to show me around the ruins of its crumbling castellum.

Each village along the winding road west of here to Mafraq, mostly blends of Bedouin and Druze populations, has an old black-stone core, free to wander but unfortunately strewn with garbage. The impressive stone buildings at times press up against both sides of the road.

The definite highlight of this basaltic string, UNESCO-inscribed in 2024, is Umm al-Jimal, (‘Mother of Camels’), an ancient crossroads for the nomads of the Badia and civilization to the west. A town with Nabatean roots, it housed a garrison in Roman times, fortified and expanded. But by the 6th century AD it was home to merchants, farmers and monks, roughly 5,000 people, many of them recycling the old Roman buildings as homes and neighbourhood churches. Many of these remained in use well into the Umayyad era until the year 749, when a terrible earthquake broke the hydraulic system at the moment trade routes shifted eastward, the Abbasid Revolution moving the focus from Damascus to Baghdad. Umm Al Jimal, like most of the castles of Jordan, immediately became a town of ghosts.

The ruins of Umm al-Jimal spread out over 30 hectares beyond a brand new visitor center. On my first trip out here (on microbus via Zarqa in 2008), a single guard had let me through the chain-link fence and allowed me to wander, then insisted on making me tea in a tent nearby. Much has changed.

Today, helpful plaques dot the ancient town along clearly-marked paths and, thanks to the Umm Al Jimal Project, you can even glimpse the old waterworks, a few of the reservoirs filled up with water again after so many centuries.

Qasr al-Hallabat

Heading south past the enormous al-Za‘atari Camp, Jordan’s largest refugee settlement (filled at the onset of Syria’s civil war), I reached the next Umayyad qasr as the sun was getting low. Qasr al-Hallabat, just a short hop north of Highway 30, is a halfway point between Azraq (50km) and Amman.

Initially a 3rd-century Roman castellum, perhaps built over a Nabatean site, it later became a palatial-monastic complex under the Ghassanids, Christian Arabs. In the early 8th century, Umayyad Caliph Hisham (r. 724–743 CE) rebuilt it again entirely, adding its waterworks, a mosque, and a nearby bathhouse: Hammam as-Sara, now restored. Like the other qusur, it fell into ruin after the caliphate’s collapse.

From another sparkling visitor center, I enjoyed the climb to the hilltop, rewarded with a sweeping view of the Badia and, southeast of the qasr, Hisham’s square mosque, entered through a graceful arched portal, beyond which lies a likewise elegant mihrab.

Stepping into the palace itself, many of its blocks inscribed with Greek (recycled bits of the Edict of Anastasius I (r. 491–518 AD), I wound to its furthest courtyard on the west to find a beautiful floor mosaic in Byzantine style.

A strictly ‘desert castle’ tour might end with al-Hallabat, but at least one more qasr still lay ahead for me, almost back where my trip began.

Zarqa & the Hajj Route Forts

On a stopover in Zarqa, Jordan’s second city yet well off the tourist radar (most passers-through see only the bus station, linking Amman to al-Hallabat, Azraq and Mafraq. A conservative bastion, its reputation has been marred by some unfortunate associations, with native son Abu Musab al Zarqawi (of Al Qaeda fame, killed in Iraq in 2006) and the build-up to Black September (the final destination for PFLP-hijacked planes).

But a short hop from the bus station, Zarqa hides the hilltop Qasr Shabeeb. Originally Roman, it was put to use again in Mamluk and Ayyubid times then restored in the Ottoman era as a station for the hajj, part of an extensive network of forts to protect southbound pilgrims. Plenty more of these box-shaped castles are strung along the Desert Highway south of Zarqa. You can count on being alone on a stop at any one of these.

Though in the centre of town, it was also the case at Shabeeb. Scanning the ledger at Zarqa’s old fort, I was surprised to find how how few had passed through (the last visit days ago). Climbing to the top, the views over Zarqa’s hills are now largely blocked by high-rise apartments, but it was easy enough to imagine how for centuries it dominated the valley that winds southwest to Amman.

Amman’s Ancient Citadel

Situated as it is, looming over the very heart of Jordan’s modern capital, surrounded by city, the spectacular qasr atop Jebel al-Qala‘a (Amman’s Citadel) can’t precisely be called a ‘desert’ castle. Still, it’s among the greatest Umayyad-era qusur to be found. Credited for the domed palace here is Umayyad caliph Hisham ibn ‘Abd al-Malik (r. 724-743), builder of Qasr al-Hallabat (and perhaps ‘Hisham’s Palace’ just north of Jericho) and uncle and predecessor to Walid II, builder of the bathhouse at Qusayr ‘Amra. ‘Desert castle’ or not, Amman’s qasr enjoys—along with the nearby impressive remains of a Temple of Jupiter—some of Jordan’s most ineffaceable views.