The jagged ruins of Shahin al-Khalwati’s khanqa (Sufi lodge) first caught my eye from Saladdin’s Citadel. On the hazy horizon to the south, its minaret juts knife-like from the cliffs of al-Muqattam. From miles away, the rest of the complex disappears against the desolate ridge.

I was more than intrigued.

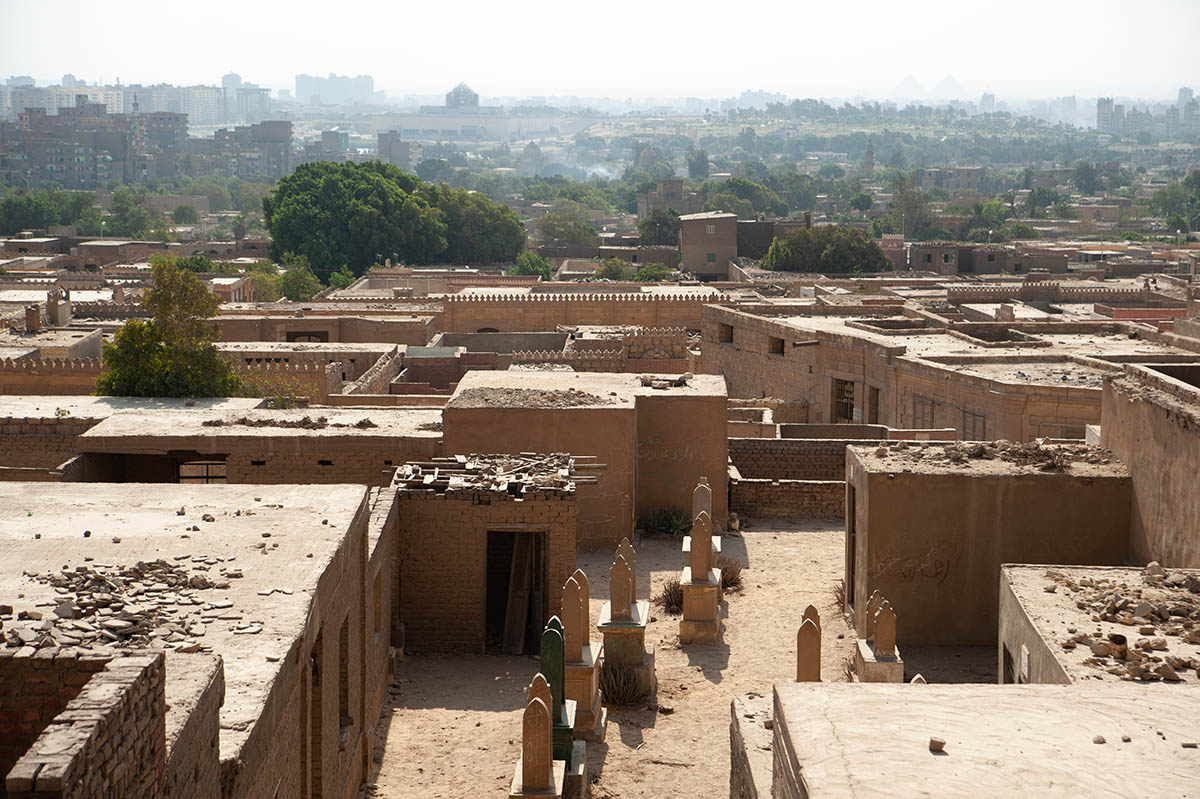

Only a few days later, it was a memorable adventure just reaching the foot of the khanqa‘s perch, alighting at the highway far south of the Citadel, soon lost in a labyrinth of silent tombs, domed mausolea and eery, dust-covered courtyards. From the last of these, I was made to flee quite abruptly after waking a pack of ferocious dogs, but only after a bit of intel: as well as the dogs, the ruin was seemingly barred by the cemetery’s high brick wall. Even if the wall could be cleared, I wasn’t sure that a scramble to the ruins was even possible. A climb would be risky.

Still, in my slow but high-adrenaline retreat, I told myself that I’d soon be back. Near the highway, my pulse was still pounding when I reached an inhabited street, spotting two men on a roof. Remembering my recent luck with the pigeon people, I waved and pointed. They welcomed me up with a wave back. From their perch atop a jerry-built high-rise they could see this whole southern stretch of Cairo‘s City of the Dead—Al Qarafa. When I asked if they’d seen any tourists around here, (to my deep satisfaction) they shook their heads no.

The serrated outline of the ruins was still fresh in my mind when it popped up again that night in the Khan al-Khalili. I was there to peruse old postcards and faded prints in a crammed, vintage store. Striking as the site is, it set me aback to see the place featured in a photo at all—all but ignored as it is by Cairenes at large, hardly noticed to the east of the southern autostrad, an outgrowth of the ridge.

Even more so, it was a small touch of detail in the card that impressed me: its two weathered domes were capped in a lively green.

Hiding in Plain Sight

Years later, when searching for background on the web, my own stock photos topped the scant results. Little was known, it would seem, beyond the major bullet points: it was a mosque-madrassa-mausoleum, built in the early 1500s by a Mamluk soldier, a favorite of Sultan Qaitbay (1468–96): Shahin al-Khalwati, an avid alchemist and a devotee of the Persian Khalwati order (from the Arabic term khalwa: withdrawal, ritual distancing from the world). Shahin, it’s said, spent his final years here, looking out over the city in self-imposed silence.

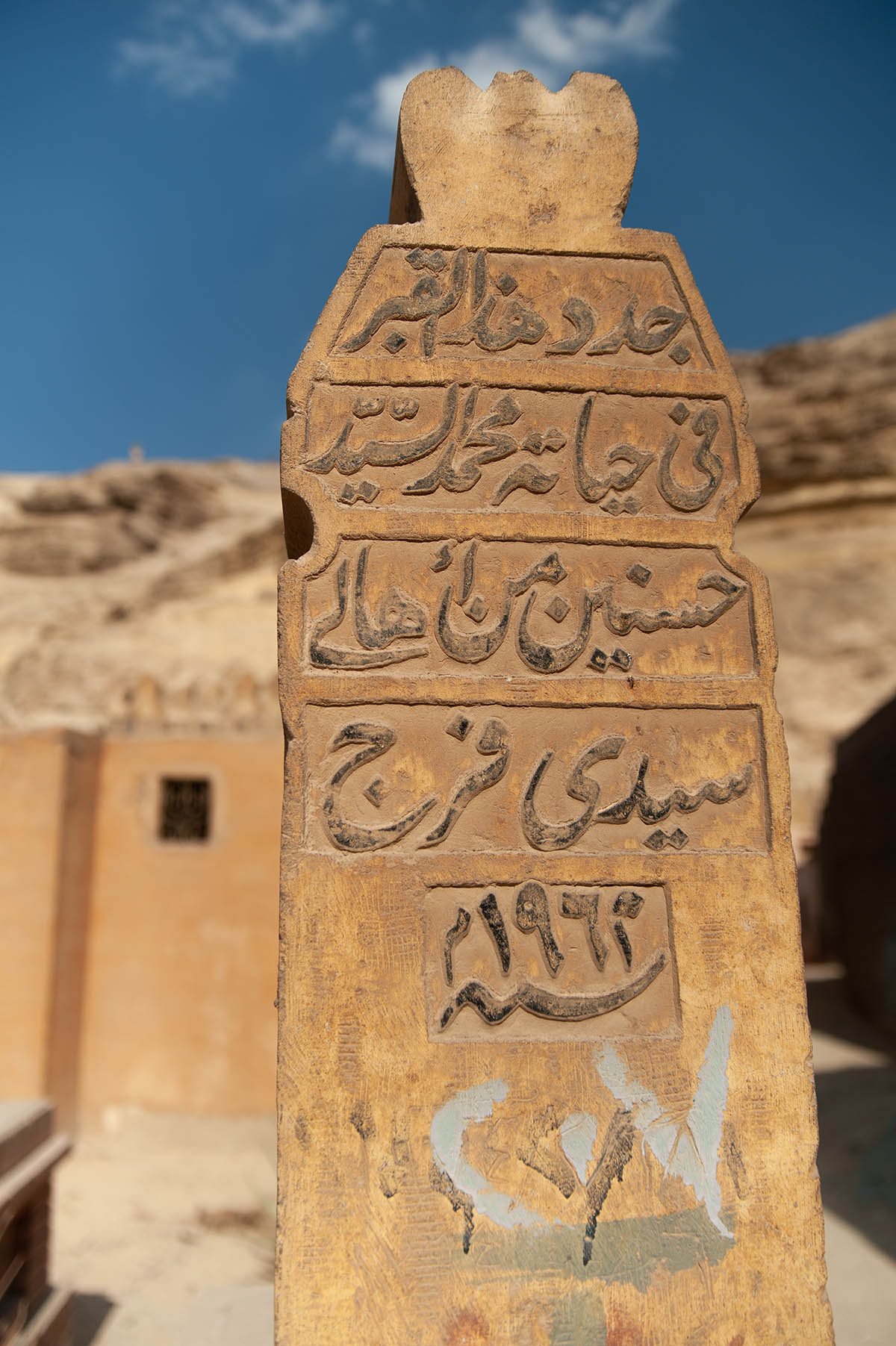

It was one of at least a pair of Khalwati khanqas or zawiyyas to spring up along Cairo’s fringes in the early Ottoman era, when actual power remained tied up in the centuries-old Mamluk order. And the Khalwati, of course, were far from the only tariqa (order) to plant roots in Cairo’s City of the Dead. The natural cul-de-sac beneath the cliffs where Shahin’s great ruin towers today, filled to the brim with graves, was known as Wadi al-Mustadʿafin (the ‘Valley of Wretches,’ the ‘Valley of the Oppressed,’ or the ‘Valley of Those Vanquished by the Love of God’), luring recluses of various classes and stripes to draw nearer to God through dhikr (remembrance).

Right at the foot of the cliff, one such order that survives still holds the annual mawlid of a 13th-century saint and prolific poet (unknown to the West but considered among the greatest here, on par with Ibn ‘Arabi, Suhrawardi and al-Hallaj): `Umar Ibn al-Farid (1181–1235). Long before Shahin or the Khalwati, Ibn al-Farid, another non-Egyptian, refused Ayyubid offers of patronage in favor of a humble, secluded existence here, tucked against the rugged, southernmost edge of the so-called Valley of Wretches.

On two visits in 2017 and 2018, I just missed the mawlid of Ibn al-Farid. A groundkeeper talked up the event, attended by a few hundred devotees. To kick off the mawlid, they march through the City of the Dead to crowd the small courtyard of the poet’s domed shrine.

On the first failed visit, I’d learned of a ladder kept nearby for reaching the khanqa. But retrieving it to scale the cliffs, at least that day, was forbidden—’security,’ the man shrugged.

Third Time Lucky: The Ascent

Unlike all over visits, the return in 2018 was made in company. Thanks to a local friend, a little negotiation over tea (in the courtyard of the shrine of Ibn al-Farid, still strewn with signs of the previous week’s festivities) and one very long ladder (fetched within seconds of striking a deal, about 200 pounds), we’d soon cleared the wall and my pulse was pounding as each step pulled us higher over the cemetery floor.

After clearing the entrance to the 500-year-old complex, the groundskeeper explained that we’d get ten minutes and only ten minutes, but yes: we could climb the minaret if we liked. But he warned not to point any cameras at the whitewashed al-Juyushi Mosque to the north, just past the similarly brilliant al-Lu’lu’a Mosque: a military zone. From the grim-looking watchtowers behind the barbed wire it was almost certain that we were all being watched.

I tried to forget this fact as I hurried through the rubble to climb a bit further up the barren hill. Alone for a moment amid the wind, picking up in the darkening dusk, I was swept by the view from here—transformed since the time of Shahin, when large tracts still separated Fustat from the faded outline of Saladdin’s Citadel, rising like a mirage over the traffic-choked highway to the north.

There was just enough time left to take up the groundskeeper’s offer. Together, we spiralled up the narrow steps of the pencil minaret, agreeing with forced laughs that we could feel the 500-year-old tower swaying with the wind. We hardly lingered at the top. But I did catch a glimpse of the graveyard dogs far below, stirring from sleep in the tomb-studded courtyards, the kings of the Valley of Wretches.

Back on solid ground, I was met right away by the groundskeeper, who nodded to the northern gate and our imminent descent. It was clear that I’d need to return for another ten minutes. I hadn’t had nearly enough of Shahin al-Khalwati’s incredible view.

*Update: Since my latest visit, I’ve noticed from afar that a (permanent?) wooden ramp now connects the hilltop ruins to the cemetery below. It’s possible that Shahin al-Khalwati’s khanqa has finally arrived on the map.