Seen from the harbor, the spire of Aarhus Domkirke juts head and shoulders over the medieval town, beneath it the twisting cobblestone streets of Aarhus’ old core, the Latin Quarter. It’s the tallest, longest, most spacious cathedral in Denmark, and high among the city’s draws. The superlatives flow: the largest frescoes in the country are here, as is the largest votive ship, the tallest stained-glass window, largest organ (though this one’s contested). And it ranks among the oldest cathedrals still in use in Scandinavia, its Romanesque precursor having opened its doors in the late 12th century.

But it isn’t the oldest in Aarhus. For the city’s first church and cathedral, you’ll have to stroll west, crossing the invisible border of the medieval town, where today’s pedestrian street ends. Now the red-brick, Gothic Vor Frue Kirke (Church of Our Lady), its predecessors included a wooden stave church and a Romanesque church of stone.

Until the 1950s, the latter—known as the crypt church—was lost to memory for more than 500 years, its outer windows half-buried, overgrown. Now fully restored, its remains can be seen down the steps beneath the altar of Vor Frue Kirke. It’s possible (though again, a point of contention) that the church is the oldest of its kind—the very first to be built of stone in all Scandinavia. Not impossible, anyway.

Over years based in Aarhus I’ve been drawn into both of these churches on occasion: shooting a wedding, a few cultural events, tour-guiding family on visits around my (inadvertently) adopted town. Once, it was an attempt to deliver my then-three-year-old daughter to a reading of sorts arranged by our day-care. Unlike most of the other toddlers, circled around the priest at the foot of Vor Frue’s enormous altar, my daughter, Kira, didn’t grasp the expectation for reverence here, jumping from her spot too fast to be caught to bound down an aisle, her laughs and shouts pealing out down up nave. Whatever it was the priest had wanted those toddlers to know, my daughter missed out.

I’ve often returned, including with Kira, who enjoys ducking down into the crypt, seeming to grasp by instinct that this place isn’t one to shout or play (as opposed to upstairs). Aarhus’ first cathedral, its seems, for both me and Kira, is a place of no small wonder—much as its far more commanding successor, the present-day cathedral to the east.

Stopping under the latter’s high vaulted ceilings in Denmark’s longest nave below its largest organ (contested), Kira cranes her neck like her dad’s to echo in a whisper: ‘wow.’

Aarhus Domkirke

From its very beginnings, Aarhus Domkirke has been dedicated to Saint Clement: the patron saint of sailors. According to legend, this 1st-century Bishop of Rome was drowned by Trajan, an anchor tied round his neck to sink him to the depths of the Black Sea. Thanks to coastal expansions, some 150m of land now separates the church from the sea (the Kattegat), but it used to edge the water.

Though not the most senior in age, Aarhus’ present-day cathedral is over 800 years old, begun in the late 12th century as a Romanesque basilica; it opened its doors in 1201 and soon replaced the older cathedral to the west. The great Absalon, then bishop of Lund, is said to have attended the founding ceremony. Its early 14th-century completion, however, was shortly followed by a devastating fire (1330), and it wasn’t until the latter half of the 1400s that the ruins were replaced with the stark, Gothic style seen today, very much inspired by the Hanseatic look then conquering the Baltic.

Outside, the imposing, red-brick exterior dominates a pair of large cobblestone squares: Bispetorv to the south, a Viking burial grounds (hence the Viking Museum nearby, where its finds are displayed); and Stortorv to the west, facing the cathedral’s main doors, at the foot of its 96-meter-high spire. Though no longer a place of whippings and beheadings, the square’s marketplace still thrives (there are shops).

Stepping Inside

Inside, the bulk of the visible structure dates to the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Some of the very first gravestones you’ll reach, just off to the right of the entrance, belong to the earliest bishops. Among these is a slab depicting Jens Iversen Lange (serving 1482-91), deserving of the credit for the cathedral’s rebirth and extension, inspired by the bishop’s travels as far south as Rome. Like much of the artwork scattered here, his tombstone was crafted in a Lübeck workshop.

Bishop Jens Iversen Lange (482-91) is also to thank for the magnificent font in the nave, crafted by a maker of bells in Flensborg. The font is held by the four evangelists, three of them animal-headed (Mark as the lion, John the eagle, Luke the ox) and Matthew as Matthew.

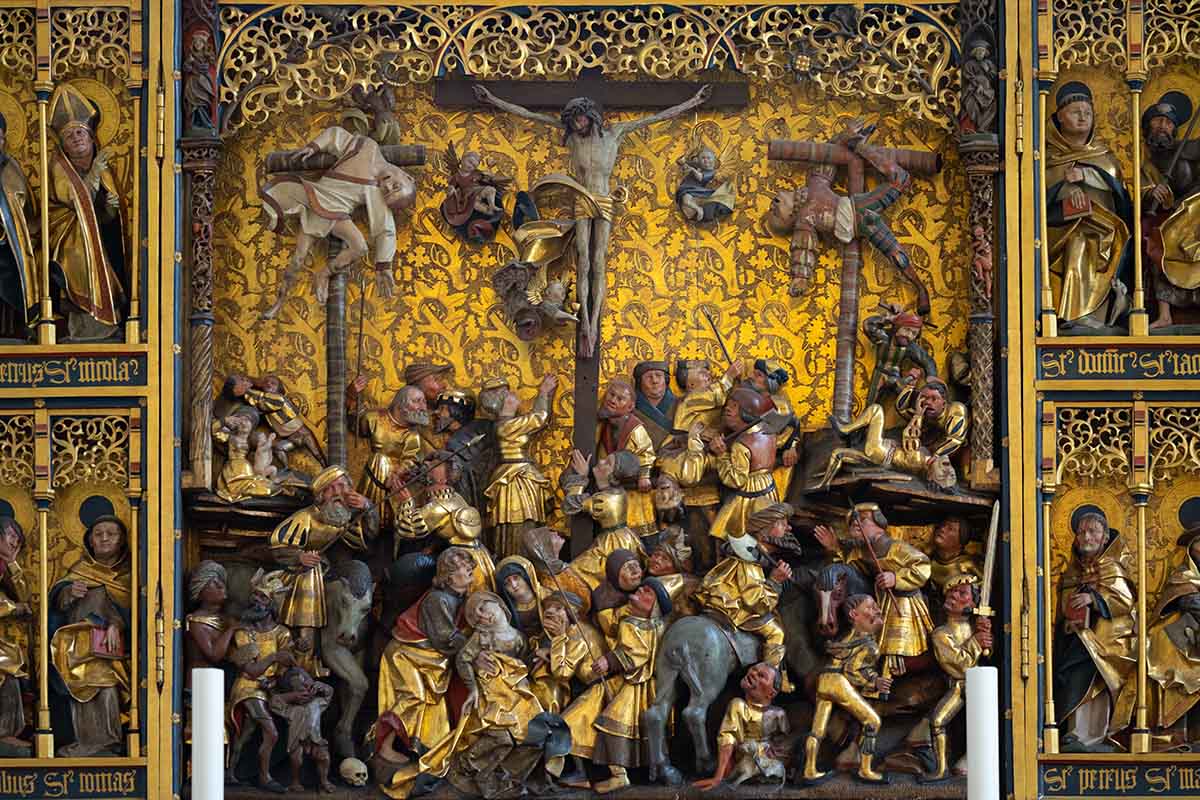

Only a couple years prior to the font’s arrival, Lange had wowed the Aarhusians even more with the unveiling of the cathedral’s eye-popping altarpiece on Easter, 1479. The work of the Lübeck-based star Bernt Notke, it was the largest of its kind in the North at the time. Right at its center are Mary, her mother and son; John the Baptist to the right, Saint Clement to the left, all flanked by the twelve. On Ash Wednesday it closes until Easter Sunday, revealing eight more painted panels, depicting the Passion. Fixed high above them all stands another Mary, awaiting a crown between a pair of archangels: Gabriel to the right and Michael to the left, shown in the act of slaying his dragon.

Marking the point when the Reformation overran Denmark, the priestly pomp of earlier tombs was stripped from those that came after, beginning with the tombstone of Bishop Mads Lang (1536-1557), the first Lutheran bishop in Aarhus. The year he took office, Denmark was Lutheran by royal decree. Priests were ousted from their quarters and sermons switched from Latin to the flat, muddled local tongue. The elaborate frescoes adorning the walls and ceilings of the church were concealed.

Tombstones and Epitaphs

Of the solemn, lay tombs up the aisles, studding both walls and floors, some are grander than others. The tombstones of Erik Podebusk and Sidsel Oxe, placed right by the altar just right of the high choir are among the most stunning (marked 1576), despite being hit mid-construction by a nationwide ban on ‘pralegrave’, gravestones deemed boastful, forbidden by King Frederik II in 1576.

But there’s one that has always caught my eye, despite being relatively simple. I’ve taken roughly the exact same photo of the slab at least a dozen times: On the wall in the aisle just north of the choir, it’s the black marble tombstone of one Mette Urne, dubbed ‘the black widow.’ Her husband was known to have died in a Swedish jail in 1564.

Nearby, another striking slab shows Erik Bjørn og Birgitte Urne, betrothed when they died in a shipwreck in 1577. He was eight years old and she was four, yet both were immortalized as adults.

The tombstones and bourgeois epitaphs, mostly Baroque, continued right up until 1805, when their like was banned altogether inside Danish churches by the enlightened King Frederik VI.

The Frescoes of Aarhus Domkirke

Just as the tombstones, the cathedral’s mishmash of frescoes are too much to absorb on one visit. To thank for their clear preservation through the years are the same righteous zealots who hid them with buckets of paint in the early 1500s. Their deed, it turns out, was somewhat easily undone. Almost 500 years later (toward the end of the 20th century), the bulk of the colorful frescoes was revealed, amounting to roughly 220m² of late medieval art.

The hardest to miss are high on the western wall of the southern transept. Saint Clement is seen with the anchor that drowned him. Beside him to the left is a colossal, bearded Saint Christopher: the ‘Christ-bearer’ and the traveler’s patron saint. An obscure, 3rd-century Caananite convert-cum-martyr (and reported as an actual giant!), Christopher seems to have found his real following—of all places, in Scandinavia—a thousand years after his death.

Advent of Christianity in Denmark

Christianity’s inroads to Denmark were blazed as early as the 9th century CE. It picked up momentum in the 10th and 11th, its power cemented by the conversion of Harald Blåtand (Bluetooth) Gormsson, Denmark’s first Christian king (r. 958–986). Just a few decades separated Bluetooth’s rule from the close of the Viking age, capped off with a bang by another great Harald (Hadrada), commander of, among other things, memorable nicknames: ‘Thunderbolt of the North,’ ‘Burner of Bulgars’ and ‘Hammer of Denmark’ to list a few. By the death knell of the Viking Age in 1066, when the Hammer’s invasion of England was crushed (just weeks before the Normans succeeded), Denmark was already liberally speckled with churches of timber. It was in that same decade, however, that stone began popping up in church construction. And the remains of perhaps the very first church built of stone in all of Scandinavia is here in Aarhus, only a short walk west of the cathedral.

Aarhus’ Ancient Crypt Church

Almost a thousand years old, the original Romanesque church was built on the burnt-out ruins of a stave church in 1060 AD. For the distinction of being the very first Nordic church of stone (contested), Harald Hadrada is at least partly to thank. It was during the Jutlandic raids of this ‘Hammer of Denmark’ (though he never took Denmark) that the stave church was burned to the ground. To replace it, a triple-apsed, tripled-naved church of ashlar and fieldstone was built. It was richly adorned with frescoes, though these didn’t survive quite as well as others.

Mostly standing-room-only, the church’s size meant it wasn’t to last as the cathedral for long. Aarhus was a regional hub on the rise. Just a century and a bit later, the seat of the bishop was moved from here to Stortorv.

The Dominicans arrived on the scene soon after, taking control of the old church and expanding the complex. The main church became known as Skt. Nikolai Kirke (Saint Nikolas Church), only reconsecrated as Vor Frue (Our Lady) Church in 1558. In enlarging the original into the Gothic-style church that largely appears today, the Dominicans increasingly used the vaulted crypt as a cellar of sorts, a storage room. It filled with junk and debris over the decades, at some point forgotten completely.

In 1955, a gardener was called in to rein back the overgrowth weighing down the walls. Clearing away shrubs and digging a bit, he stumbled on three strange openings that he was amazed to discover were windows.

A reconstruction was soon decided upon, using the same stone from Skanderborg as for the original church. High on the walls, a horizontal line shows the extent of the surviving structure and where the modern reconstruction begins.

Appearing suspended in the blackness at the furthest end of the crypt is a striking, gilded cross. It’s a copy of one crafted at the same time as the crypt beneath Vor Frue Kirke was built: the gilded Åby crucifix. The original, found just outside Aarhus, can still be seen in Copenhagen’s National Museum. Looking closer, you’ll see that it’s not the familiar Jesus of meekness and suffering. It’s a conquering Jesus, perhaps crafted before a visual reference of Christ had reached this far north, a Christ on the cross that evokes a martial, warlike, spirit; a Viking Jesus: braided beard, large hands, horned crown. The artist, it appears, was channeling Thor, god of war, reflective of the era’s bridging between old and new gods, rites and faiths.

Vor Frue Kirke

I’ve been asked to take photos for a wedding and several literatary events over the years inside, both within the main church and on the lawn of the adjoining cloister that served the Dominican complex (now it serves, at least in part, as a home for elderly Aarhusians).

The time the toddlers from my daughter’s day-care were sitting cross-legged on a carpet by the altar, listening to the priest, I was sprinting up the aisles after Kira, enjoying the sound of of her echoing voice.

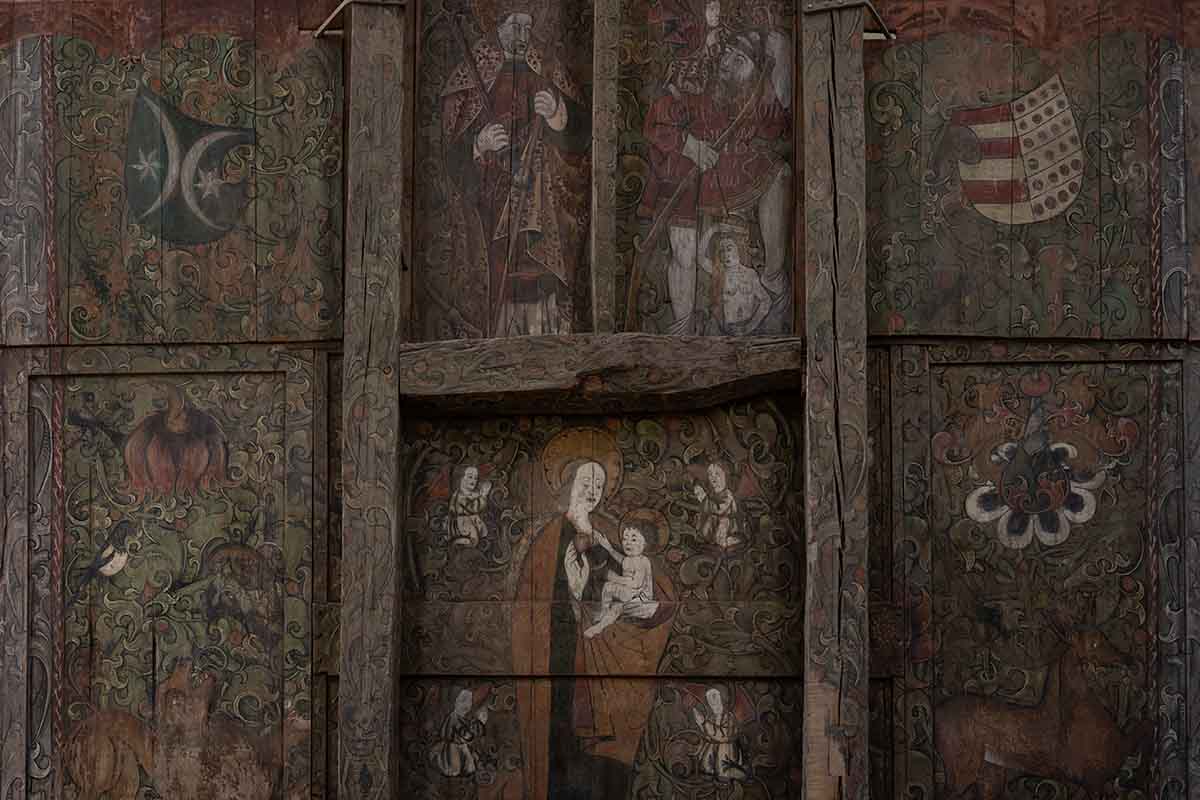

The large, golden altarpiece over the spot where the kids sat is at least 500 years old, gifted by a Danish queen. A trio of wise men are shown visiting Mary and Joseph in the manger. At the center, the crucified Jesus is flanked by the two thieves, twisted like pretzels on their crosses. The apostles and a pair of Dominicans fill the side panels.

Just left of the altar, one of many coats of arms on the walls, belonging to the wealthy benefactors, depicts a trio of lions: the insignia of King Valdemar IV (1300s), dating from before his ascent to the throne. It appears on a few coins today as well as the burgundy Danish passport.

As at Domkirken, Vor Frue’s whitewashed walls are decked with the brooding, Baroque epitaphs of wealthy Aarhusians.

The Cloister Church

Vor Frue Kirke and the Crypt Church are actually only two of three churches at the complex. Despite all the years and visits, it was only this summer that I first stepped into the third: Klosterkirken (the Cloister Church), hidden away on the southern end of the courtyard, where the bones of centuries of Dominicans have been found. A runestone also found here is evidence that this was a node of traffic as far back as the Viking Age.

Belonging to the monks, this tiny church has its own impressive collection of medieval frescoes, some portraying the contrasts of real-world grind against contemplative, monastic life. The friars were expected to lead silent, celibate, meat-free, mattress-free lives, sleeping with robes and shoes on (the worst part), discouraged from light-hearted laughter. When failing in the latter, they were supposedly punished in the form of hymns or ‘blows to the back.’

The oldest elements in the room are the pillars, ‘loaned’ from somewhere far to the south.

Postscript: Return to the Crypt

On Kira’s first visit the crypt, just weeks after our failed attempt to have her join her peers upstairs in reverence, her voice dropped immediately to a whisper as we descended the steps beneath the choir. As usual, there was no one else around. She pointed into the murk up ahead, where a few lit candles gave the darkness a mystical, old-world glow: ‘Wow,’ she said, transfixed by the golden, faintly glimmering warrior-Jesus. Forgetting to whisper this time, she exclaimed with pure wonder, ‘the queen!’