A shorter and much-altered version of this post is featured in the Lonely Planet Jordan (2024). Find an extended account of my experience along the Wadi Rum Trail on BBC Travel.

The afternoon sun was sinking into the tops of the ochre cliffs as we slipped out of Wadi Rum village, headed south, bounding along a highway of tracks in the sand in Salman’s old 4×4 truck. While subtly shifting the wheel to dodge dunes and shrubs, he scrolled and poked at his phone, looking rushed. The network wouldn’t last. He had several more guests arriving later in the village. In fuzzy old memories he’d joined his family for weeks out here, he’d told me, recharging deep in the desert. Now, in full charge of the family’s tourism business, internet connection had become a prime concern.

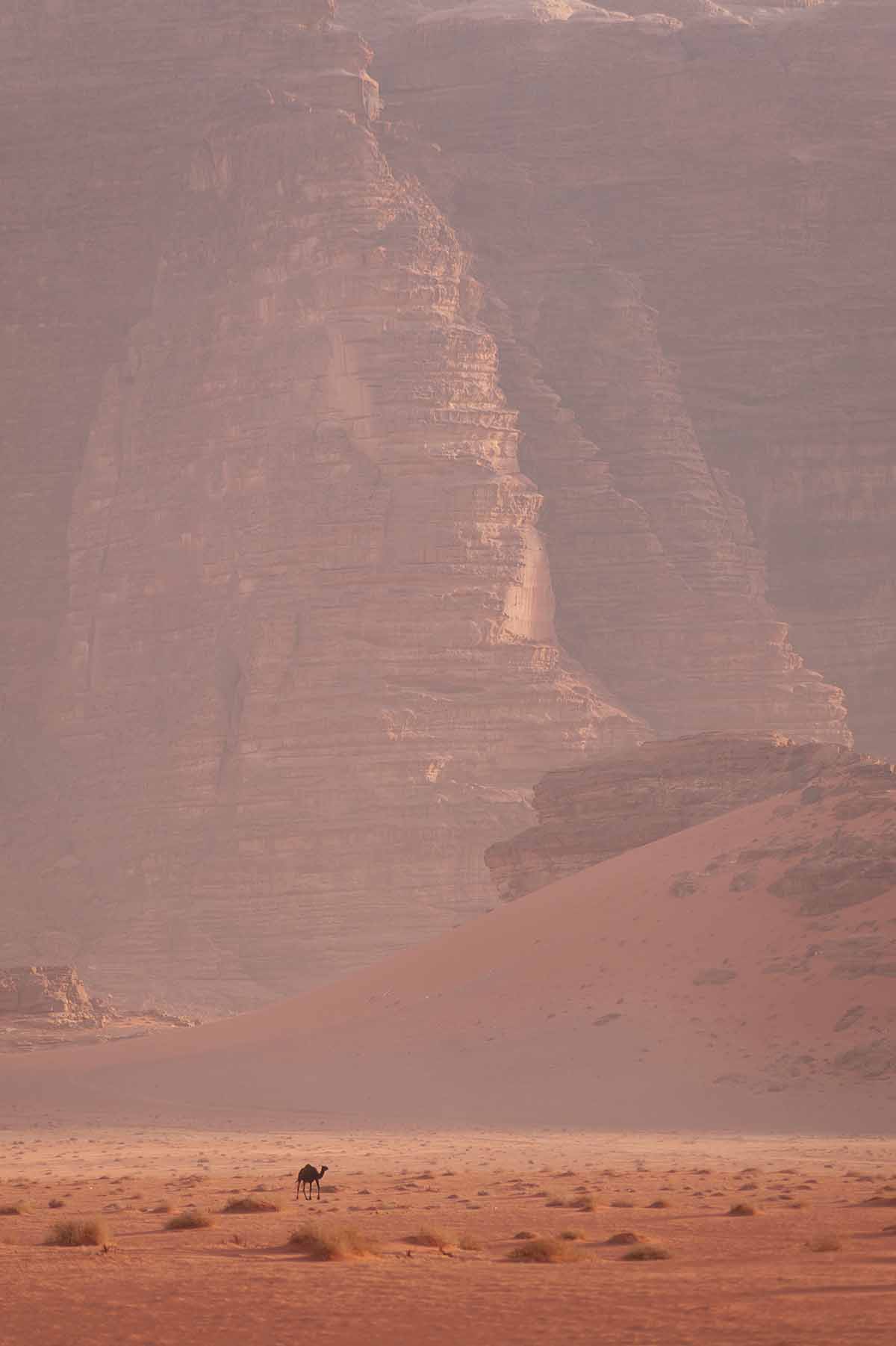

Rounding the huge granite plinth of Umm Ishrin, the Khor al Ajram—perhaps the greatest of Wadi Rum’s natural highways—opened to reveal a sprinkling of clustered, black camps on the horizon, some far more conspicuous than others: Martian space bubbles popping in brilliant white against the bases of enormous cliffs. Yep, there’s a lot more camps now, he nodded in agreement, adding that quite a few are most definitely not legal.

The jeep tracks soon thinned, the red sand turning white. Salman pressed the gas pedal harder. His old jeep shuddered as we sped through the mouth of a particularly sheer-walled canyon, popping out after some time onto the far, southern side, another grand highway but this one devoid of camps: the dizzyingly vast Wadi Sabet.

That’s it, he pointed at the brooding, pointed hulk of burnt, reddish rock: Umm ad-Dami, Jordan’s highest peak, brooding just next to the Saudi border.

I asked about its name. Ibex was plentiful here—perhaps the name was to do with hunting? No, the story had escaped him at the moment, but he guessed it was linked to the ancient Bedouin code. Known simply as damm (‘blood’), serious (violent) disputes are traditionally brought before the Bedouin sheikh, overseer of the unwritten, eye-for-an-eye law to uphold the tribe’s values of justice and honour. In Jordan’s Bedouin strongholds, the code still has a few teeth to this day.

I’d first met Salman ten years prior, while lending a wholly unqualified hand on the family’s tourism website. He’d been generally buried in studies, so his brothers more often would join me on desert jaunts: tending to camels, gathering wood, spending nights in the family’s permanent goat-hair tent camp. The coarse, black fabric was straight from Maʿan’s souq, stacked high with all manner of manufactured supplies, sparing what had amounted—in the not-too-far past—to several years of strenuous weaving.

The camp’s new bathroom block was fitted with solar panels, affording hot showers to guests. We had dinners of zarb, meat chunks cooked in the sand, providing tourists with a stylized taste of tradition. Salman’s brothers would pluck at the oud and we’d sleep under the stars, bounded by the blackness of the cliffs, or squinting at the dunes beyond for the flitting of desert foxes or jinn.

Salman appeared enlivened as his jeep closed the gap between us and the crumbling peak, not another 4×4 in sight. Perhaps it was the apparent desolation around us that led him to recount a recent trip to Bali, infusing him with glee at the memory–a whole new world, he said, recounting the greenery, the shower-force rain. When he cut off the engine, we were less than a mile from the Saudi Arabian province of Tabuk.

Bedouin Icons

Comprising a full half of Transjordan at its founding, the Bedouin have long been the Hashemite Kingdom’s ‘backbone’, ever loyal to the crown. Thanks to a century of government efforts, a vanishing few, however, remain truly nomadic. Most have settled in towns or along outskirts, taking up sheep and goats as camel herds dwindle.

While the vast majority of the country’s Bedouin hail from the endless steppes of the Badia, it’s the relative handful residing in Wadi Rum that are certainly best-known abroad. As their ancient predecessors, Salman’s Zalabia clan was lured to the area by the springs that tumble at Jebel Rum’s base, etched with faded Thamudic, Greek and Nabatean scripts.

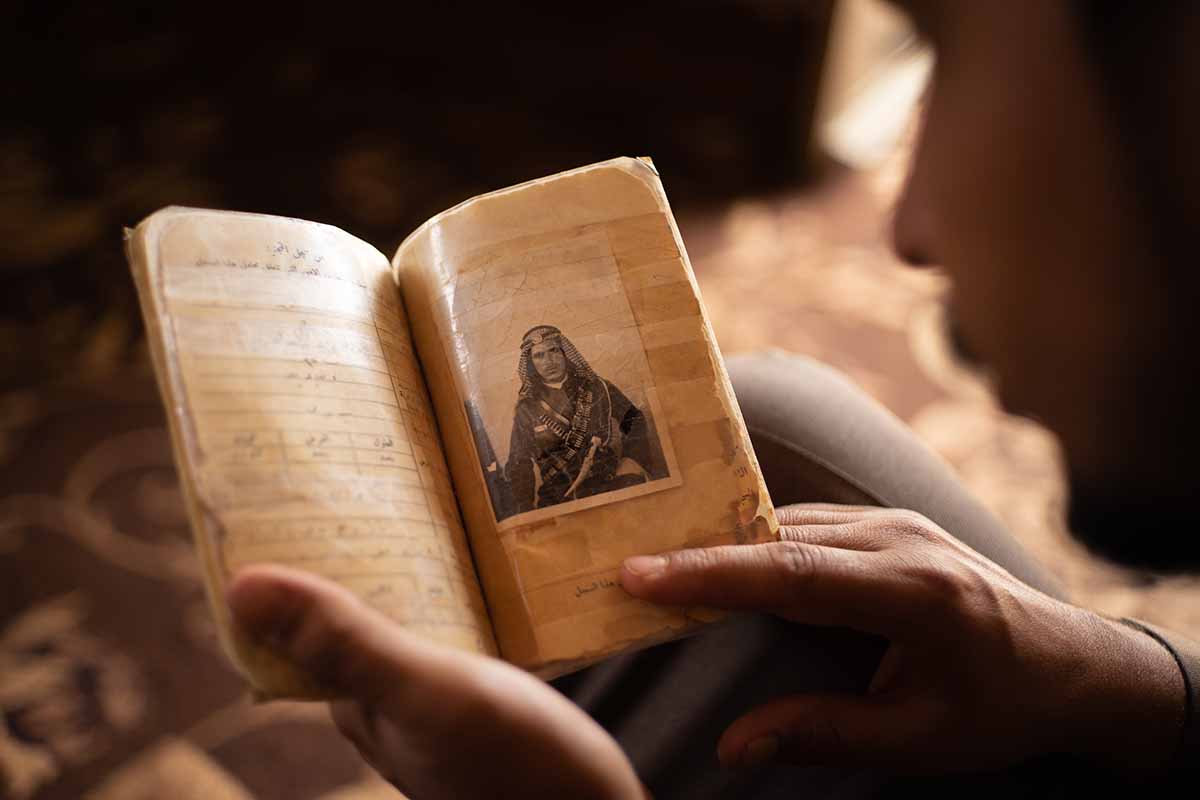

Prince Faisal enlisted the various tribes roaming here to join the Great Arab Revolt. Soon afterwards, Salman’s own grandfather was among the very first enlisted in the newly formed Hashemite force. A few decades later, in Lawrence of Arabia, the dreamscapes that enchanted Colonel T. E. Lawrence were broadcast on the big screen. When filmed, today’s village was little more than a huddle of hand-woven tents.

The road and the permanent village it linked arrived later. Among the first to attend the boy’s school here was Salman’s father. His children followed suit. Unlike him, however, Salman didn’t need to scour the desert for his family each time school let out. Instead, a two-minute walk brought him home, a concrete plot on the village’s eastern end.

The tourism wave of the late 20th century continued its swell into the next. Despite the vicissitudes of regional unrest, the spectacular landscapes only ramped up their cinematic presence, further wedding in the world’s imagination the legendary Bedouin to Rum’s soaring cliffs.

Among a spate of films, the desert here starred in the sci-fi blockbuster Dune, which didn’t stop there: its fictional Fremen were a transparent phantasm of the Bedouin themselves. First-time visitors should be forgiven for packing a raft of glamorized notions of Wadi Rum’s tribes, the Bedouin—as settled civilization’s perennial other, as emblems of separate, lost world.

Ascending Umm ad-Dami

The family’s tourism website was broached for a moment on the hike up the mountain’s eastern slopes, cloaked in shade. Most camps now had far better sites, he admitted. Instant booking sites ruled, though he still preferred the old clunky website himself, however badly out-of-date.

But some things hadn’t changed. His young daughter, he mentioned as we climbed toward the light, had recently received the old protection against venemous stings—her maternal grandmother had mixed the charred remains of a scorpion with oil, then placed it on the child’s tongue. Religious faith remains firm as well. In tourism, Bedouin women remain almost entirely out of sight. And while their family plot was increasingly crammed with new concrete homes and parked SUVs, they’d kept a few camels. Recalling one of his grandmothers’ painstaking, barefoot treks for potable water, Salman seemed to sigh at the distance between her life experience and his. As his brother has said, the past was a dream—in some ways a nightmare. Indeed, there’s plenty to spark real gratitude today. For one, Salman is thankful to call this stunning corner of Jordan home in the 21st century. His daughter would study. God willing, she’d see a fair bit of the world beyond.

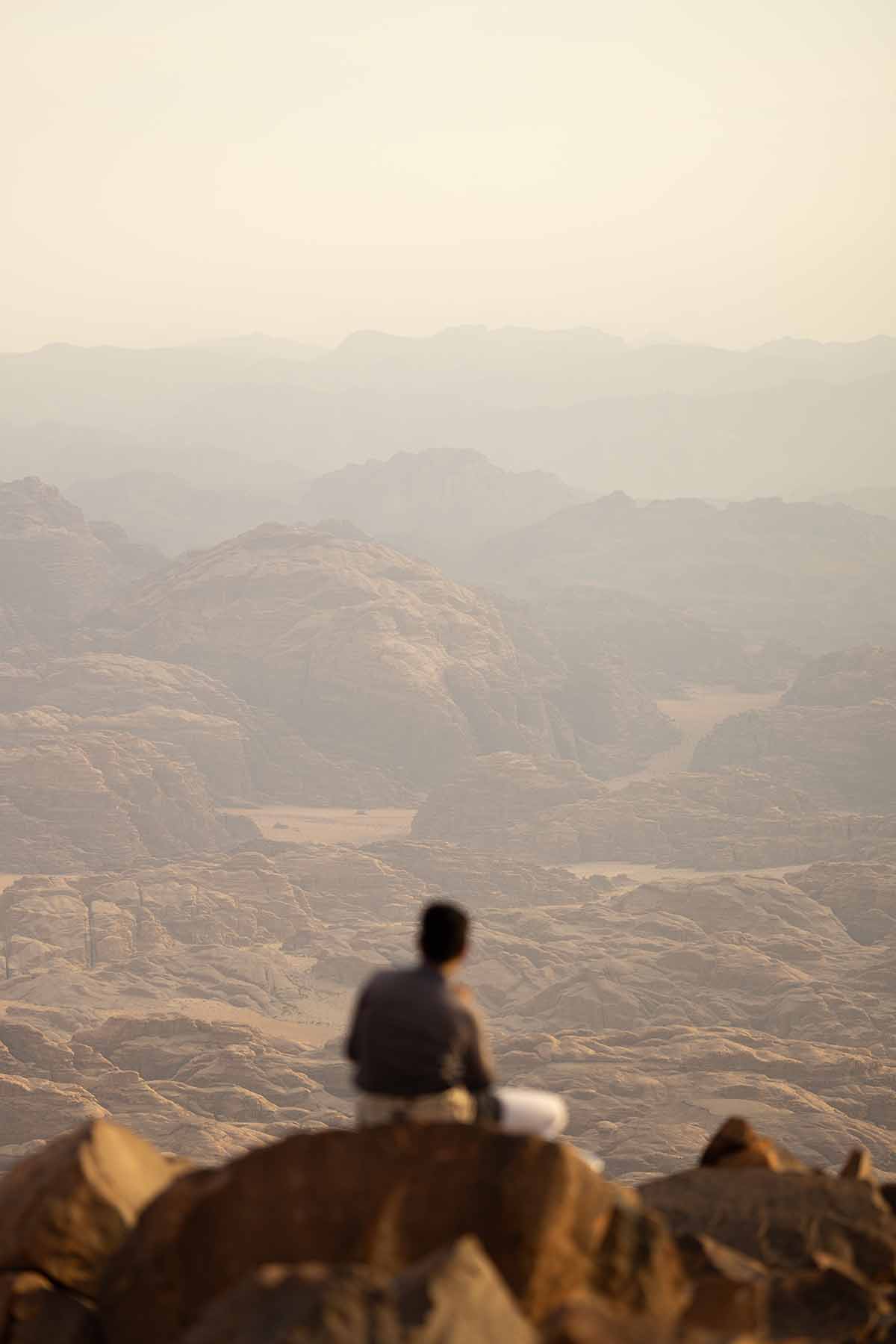

Stepping into the sunlight, I fastened a scarf to my head as Salman donned a khaki, rimmed cap. The clouds burst with color as we scrambled the final stretch up the bare ridge, each choosing a boulder to stand on. Looking west at the series of golden ridges, I wondered if the mountain’s name—Umm ad-Dami—had as simple an origin as the burnt orange tinge of the rocks at this golden hour. The peaks faded into the blinding sky at the western horizon, towering over immaculate sands far below, smoothed by distance. The wind picked up, a bit warm but still very much welcome and there was a touch of damp at the corners of my eyes.

Our phones buzzed. The message: ‘Welcome to Saudi Arabia’. Smiling, I turned to Salman, who was standing tall on his rock, looking away, facing straight into the wind and the sunset, his smart phone held up high.